Cities are crucially important for the human future and for world mission.[1] So starts the Call to Action in The Cape Town Commitment in its statement on cities. As recently as the 1990s, commentators announced the ‘end of geography’,[2] and ‘a flatter world’,[3] as technological change was meant to increase homogeneity and make cities less important.

It did not happen. In fact, the ‘world is getting spikier’, as the increasing significance of the ‘local’ is working alongside the ‘global’,[4] reflecting the increasing importance of human interaction in the sharing of knowledge and local scale, to make cities the critical sites for migration and development. Cities are not just centres of power, wealth, culture, and employment. They are also places that concentrate the poorest of the poor in an ever expanding sprawl of informal settlements and loom with increasing significance in the global climate change agenda.[5]

As The Cape Town Commitment points out, cities ought to lie at the heart of any 21st century strategy for global mission. This article offers four basic foundational elements for an effective response to this challenge.

1. Understanding urban growth implications

It is vital to examine the evidence of urban growth and its implications for Christian mission. At first sight this might seem obvious. Yet, a recent strategic review for Global Connections (the UK network for world mission) found that among global mission agencies with a UK base, a rural paradigm of mission still predominates:[6]

- Western-based mission agency websites communicate clear messages and images inviting people to join them to reach out to people, to share the gospel, particularly in rural places.

- Yet the milestone was passed around 2008 where over half the world’s population was urban.[7]

The UN expects this proportion to rise to 70% by 2050,[8] with some 200,000 on average currently being added to the world’s urban population every day; 91% of these in the global south.[9] Whilst it took London 130 years to grow from 1 to 8 million, Dhaka took 37 years and Seoul only 25.[10]

As The Cape Town Commitment points out, the city is also where four crucial groups of people are most likely to be found – young people, the most unreached who have migrated to the city, the ‘culture shapers’, and the poorest of the poor. The mission community needs to recognise the evidence and develop a strategic response to urbanisation in the world today.

2. Avoiding a focus just on global cities

Global cities are the best-connected and highest-profile places on the planet. As Janice Robinson points out in Ordinary Cities,[11] it is a feature of the Western approach to urban development to emphasise the hierarchy of cities:

- At the top of the hierarchy are the global cities (particularly cities like London, New York, Paris, and Tokyo) – the key hubs for the knowledge economy that lie at the heart of the global economy.

- Some way down the pecking order lie the expanding number of mega-cities (cities with over 10 million inhabitants) of the global south, like Johannesburg, Lagos, Karachi, Mexico City, Dhaka, and Mumbai with their complex mix of economic opportunity and massive social, environmental, and spiritual challenges.

- Even capital cities of countries in economic transition, like Tbilisi (Georgia) and Yerevan (Armenia), account for some 75% of their national economies.

Yet if the focus of mission simply shifts from the rural across to these cities, something critical is being missed: more than 53% of the world’s urban population alone lives in smaller cities of fewer than 500,000 inhabitants.[12]

3. Seeking to understand the urban challenge

We need to understand before starting to act. As David Smith has pointed out: ‘Unfortunately, Christian reflection on the urban challenge has often jumped far too quickly to the practice of mission within the city, and so has lacked adequate research and understanding of the nature of the urban context’.[13]

More attention ought to be given to appreciating the nature of urban change and what it means for mission. As the Global Connections study indicated, one reason for the dominant rural paradigm is that rural places appear less difficult to work in and easier to build community in.

Yet it is the complexity and diversity that makes cities so fascinating. To really understand the urban context, it is vital to travel beyond the capital city. Because of its international connectivity and urban scale, the capital city, even in the global south, is likely to replicate and even exaggerate many of the characteristics of its Western peers, good and challenging alike.

However, to appreciate the character and spiritual pulse of a country properly, it is best to set out for the secondary cities and seek to understand how cities have been shaped by their institutional, social, and cultural development over their histories.

Part of the interest of medium-sized and smaller cities is that they do not perform as a single type. In fact, their different histories may lead them to play different roles within their national urban system.

In a study of English cities, medium-sized cities were allocated to typology categories based on their dominant characteristics and historical pathways.[14] This approach has limitations: cities often have characteristics of two or more categories leading to some simplification.

Nevertheless, the study drew out the significant richness of variation in place-characteristics among cities in the English urban system and the way they have been shaped by history.

The typological categories identified were:

- Gateway city – provides connections for goods and/or people to the international economy (eg the location of a port or airport such as Grimsby or Hull).

- Industrial city – historically developed around one or more dominant industrial sectors as a consequence of physical geographic advantages or proximity to raw materials (eg Blackburn, Burnley, and Stoke-on-Trent).

- Heritage/tourism city – attracts national and/or international visitors owing to its advantageous location or its historical, cultural, and architectural heritage (eg Bath, Blackpool, and Worthing).

- Regional services city – historically has grown through supplying employment opportunities and retail and other services to its wider region (eg Chester, Gloucester, and Norwich).

- University knowledge city – contains a leading university with expertise in science and technology and the capacity to promote innovation and clusters of spin-off companies in the local economy (eg Cambridge and Oxford).

- City in a capital- or large-city region – historically benefits from its physical connection to a capital- or large-city region, by specialising in complementary knowledge-intensive industries that give the larger city its comparative advantage in the national or global economy (eg Aldershot and Reading).

The university knowledge city and city in a capital-city region tended to be the strongest economically with higher productivity firms and a more highly paid and skilled workforce. The gateway and industrial cities tended to be the weakest with opposite characteristics. The other types came in-between. Socially and culturally, all types offer distinctive challenges and possibilities.

Such an approach is most valid in a Western European context, where there has been a long and varied evolution in the role and development of cities and where the urban system is becoming increasingly heterogeneous in character.[15] Beyond Western Europe, the picture may look somewhat different. In Eastern Europe, for example, two types are likely to dominate, reflecting former Soviet patterns of development: regional services cities and industrial cities.

In the global south the patterns will be different again. Nevertheless, as Janice Robinson points out, we might better understand all cities as ordinary,[16] in making the case that we should appreciate the depth of cultural diversity and complexity that shapes the distinctive futures of all cities. In doing so, we might avoid the Western-dominated approach of labelling cities within a hierarchy that puts the global and capital cities at its head at the expense of others.

4. Mission agency and church response

We can then begin to develop a response. For mission agencies it should begin by starting to understand, then helping to educate and communicate that the world is increasingly urban and that our contemporary response to mission needs to adjust as a consequence. It then involves both drawing together and building strategic responses from lessons of best practice. Above all, it is time for the invisible city to disappear from the image that is so frequently communicated about the nature of mission.

Churches have a critical role to play strategically and on the ground. Churches are beginning to recognise opportunities to develop city-to-city networks, drawing on natural characteristics of connectivity, density, and functional relationships across and within cities. They operate most strongly across the larger cities, such as the pioneering Redeemer City to City network.[17]

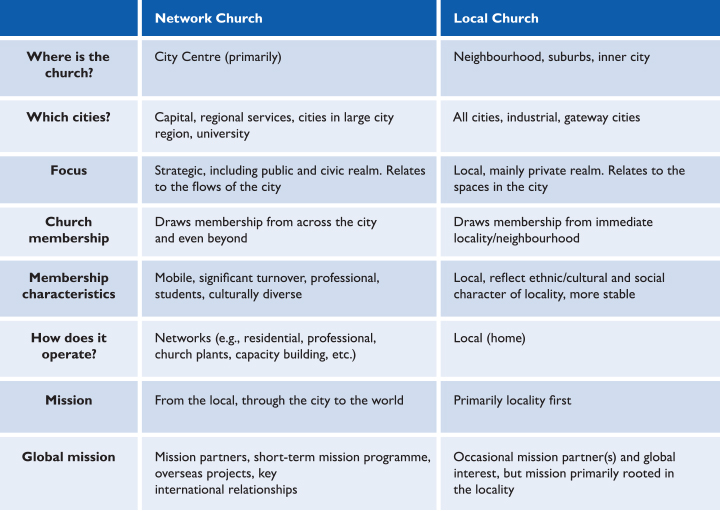

A useful distinction might be offered in the spectrum of roles that churches contribute to mission in the city. These span from the network to the local church, drawing on the natural flow and spaces that characterise the city: [See figure.]

- Some churches, particularly large city-centre churches, operate through their membership across the city as a whole and even possibly beyond. We might term these network churches, for the way that they use networks locally, in the city and internationally in mission. In the typologies described above, they may be found more commonly in university, large-city region, regional services, and capital cities.

- Other churches are more local, drawing from and serving their local community neighbourhood, sometimes in the poorer and more isolated spaces of the city. They will be found in all cities.

If these roles and relationships were mapped within the city and churches developed a better understanding of how these roles might be complemented to support each other across the city, a more strategic approach towards mission for the city might become possible.

Conclusion

The Cape Town Commitment urges that we discern the hand of God in the massive rise of urbanisation in our time and respond to this fact by giving urgent strategic attention to urban mission.[18] This article suggests four basic foundations to answer this call with an effective response which places cities at the heart of mission.

Endnotes

- The Cape Town Commitment, p. 56.

- O’Brien, R (1992) Global Financial Integration: The End of Geography, New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press.

- Friedman, T L (2007) The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, 3rd edition, New York: Picador.

- McCann, P (2008) ‘Globalization and Economic Geography: the World is Curved, not Flat’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, vol. 1, pp. 351-370.

- Bulkily, H and Betsill, M M (2013) Revisiting the Urban Politics of Climate Change, Environmental Politics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 136-154. [Editor’s Note: See also Mick Pope’s article, ‘Climate Change in Oceania: Ecomission and Ecojustice’, in this March 2014 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis.]

- See Global Connections website, available at: www.globalconnections.org.uk/missionresearch.

- Editor’s Note: See Mac Pier’s article, ‘Global City Influence: A Personal Reflection’, in the June 2013 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis.

- UN-HABITAT (2012) State of the World’s Cities 2012/2013: prosperity of cities, Nairobi, UN-HABITAT.

- Ibid.

- UN-HABITAT (2004) State of the World’s Cities 2004/2005: globalisation and urban culture, Nairobi, UN-HABITAT.

- Robinson, J (2006) Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development, Abingdon Oxon: Routledge.

- UN-HABITAT (2006) State of the World’s Cities 2006/2007: the Millennium Development Goals and urban sustainability, Nairobi, UN-HABITAT.

- Smith, D W (2011) Seeking a City Without Foundations: Theology for an Urban World, Nottingham: Inter-Varsity Press.

- Hildreth, P A (2007), Understanding Medium-Sized Cities, Town & Country Planning, vol. 76, no. 5, pp. 163–167.

- Dijkstra, L, Garcilazo, E, and McCann, P (2013) ‘The Economic Performance of European Cities and City Regions: Myths and Realities, European Planning, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 334-354.

- Robinson, R, ibid.

- Redeemer City to City Network, available at: http://redeemercitytocity.com.

- The Cape Town Commitment, p. 56.