When Billy Graham was interviewed for Newsweek magazine in 2006, he was asked what he thought was the most enduring impact of his remarkable sixty-year global ministry. To the surprise of the interviewer, he responded that perhaps his most significant contribution was the 1974 Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization and the resulting Lausanne Movement.[1]

Though Graham, the most visible and influential evangelical leader of the 20th century, had preached to huge crowds around the world and had impacted millions through his broadcasts, books, movies, conferences, etc., he had a growing appreciation for the significance of what took place in Lausanne, Switzerland, in July 1974.

This year we commemorate the 40th anniversary of that epoch-making congress, which was, in my view, the most significant world mission gathering in the Christian era. This article will explore its legacy by identifying seven factors that contributed to its global impact.

1. Historical context

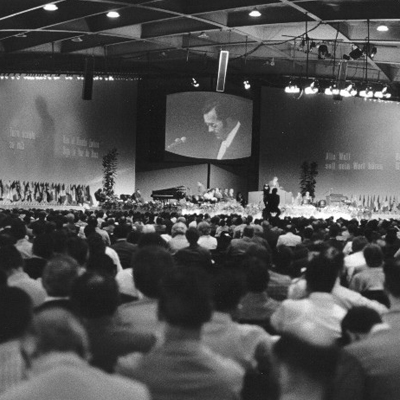

In July 1974, 2,700 Christian leaders from nearly 150 countries met under the theme ‘Let the Earth Hear His Voice’ to consider the challenges and opportunities of world evangelization. TIME magazine referred to Lausanne ’74 as “a formidable forum, possibly the widest ranging meeting of Christians ever held.”

Such a gathering could not have taken place earlier. The historic Edinburgh World Missionary Conference in 1910 brought together some 1,200 mission leaders, 90 percent of whom were from Europe and North America. This reflected the reality that the vast majority of Christians at that time were in the Northern Hemisphere. Mission was understood largely in terms of “from the West to the Rest.”

However, by 1974, thanks in no small part to the impulses and missionary initiatives of Edinburgh 1910, the church had experienced tremendous growth in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Furthermore by 1974, new political, economic, and ideological realities created the global context in which a congress like Lausanne ’74 was possible—and essential. Lausanne ’74 thus took place at a time of monumental shifts in global Christianity.

2. Leadership of global stature

Graham was the visionary and catalyst for Lausanne ’74. Without his convening power, the Congress would not have happened. Though he was the central figure, he enlisted a company of leaders with exception ability, including Bishop Jack Dain and Dr. John Stott. The latter was invited to serve as a Bible expositor and as the chief architect of the Congress document, The Lausanne Covenant.

Stott was initially disinclined to participate, but his role would prove to be most significant. He and Graham emerged as the two great figures of the Congress:

- Their respective statures as the world’s most trusted pastor/theologian and the most loved and respected evangelist/statesman would prove to embody the ethos of the Congress as a gathering for “reflective-practitioners.”

- Graham and Stott articulated the vision, calling “the Whole Church to take the Whole Gospel to the Whole World.”

- They also shaped the “spirit of Lausanne,” which Graham described as a spirit of “humility, friendship, study, prayer, partnership, and hope.”

Whereas the participants at Edinburgh 1910 had been almost exclusively missionary leaders, Lausanne ’74 was broadened to include pastors, church leaders, and scholars, as well as leaders from business, government, and the media.

3. The Lausanne Covenant

Three great contributions of global significance emanated from the first Lausanne Congress. The greatest of these was The Lausanne Covenant whose primary architect was Stott. It is widely considered the most significant missions document produced in the Protestant era, and is recognized as the most concise and commanding expression of evangelicalism. As such, it served as a uniting force and mobilizing impetus for world evangelization in the post-congress era.

4. Holistic mission

In reaction to the prominence given to the “Social Gospel” in the early and mid twentieth century by the World Council of Churches (WCC), evangelicals had neglected their historic commitment to the social implications of the gospel. That changed dramatically at Lausanne and in the years to follow through the work of Samuel Escobar and Rene Padilla, brilliant, young Latin American theologians and student workers.

In article five of the covenant, Christian Social Responsibility, Stott captures the essence of the prophetic words of Escobar and Padilla:

We affirm that God is both the Creator and the Judge of all men. We therefore should share his concern for justice and reconciliation throughout human society and for the liberation of men and women from every kind of oppression… We express penitence both for our neglect and for having sometimes regarded evangelism and social concern as mutually exclusive. Although reconciliation with other people is not reconciliation with God, nor is social action evangelism, nor is political liberation salvation, nevertheless we affirm that evangelism and socio-political involvement are both part of our Christian duty…

Forty years on, the thinking and engagement of evangelicals has changed dramatically as evidenced by the growth of ministries like World Vision International and International Justice Mission.

5. Unreached people groups

The third great contribution was the discovery and introduction of a new missiological paradigm. Prior to 1974, mission and church leaders commonly thought in categories of sending missionaries to the 150-plus countries of the world. Because it was believed that churches had been established in nearly every country, some were calling for a moratorium on missions. However, Dr. Ralph Winter challenged this understanding by introducing the concept of nations as ethno-linguistic people groups. He estimated that there were some 16,000 nations representing over 1.5 billion people who had no access to the witness of the gospel.

The result was not a moratorium, but rather a whole new movement with growing momentum for missions. This new paradigm would come to impact virtually every evangelical mission society, seminary, and mission-sending church in the world.

6. The Lausanne Movement

Perhaps the most unanticipated result of the Congress was the naissance of The Lausanne Movement itself. Graham had not envisioned this. However, in the final year of preparation for Lausanne ’74, it was evident that exciting new ideas were being developed as scholars, leaders, and practitioners from north and south, east and west were discovering one another. This found expression in a groundswell of support for an ongoing entity.

Since Lausanne ’74, The Lausanne Movement has convened two further global congresses on world evangelization:

- The second congress, held in Manila in 1989 under the theme “Proclaim Christ Until He Comes,” produced The Manila Manifesto.

- The third, Cape Town 2010, convened under the theme “Christ Our Reconciler,” produced The Cape Town Commitment.

In addition, The Lausanne Movement has convened nearly thirty global working consultations. These smaller consultations, together with two larger Lausanne Forums on World Evangelization, have produced 65 Lausanne Occasional Papers. Lausanne has also convened two global younger leaders’ gatherings. A third is planned for 2016.

Commenting on Lausanne ’74 and the ensuing Lausanne Movement, Stott wrote, “Many a conference has resembled a fireworks display. It has made a loud noise and illuminated the night sky for a few brief brilliant seconds. What is exciting about Lausanne is that its fire continues to spark off other fires.”

7. Movements within the movement

Lausanne ’74 gave birth to a global movement. It created a new sense of unity and energy for global evangelicalism, and it ushered a new epoch in world evangelization.

Seven distinct streams flowed into the Congress, each with its own history, ethos, expectations, and aspirations:

- Nearly 40 percent of participants were from church bodies related to the WCC. These were evangelically minded leaders who found a new home in Lausanne after the International Missions Council (IMC) from Edinburgh 1910 had seemingly lost its way and been absorbed into the WCC. They were attracted to the intellectual vigor and theological orthodoxy of Lausanne.

- World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF), now the World Evangelical Alliance, had a presence.

- Student movements such as Campus Crusade for Christ, Navigators, and the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES) were disposed toward a meaningful engagement with culture.

- Emerging leaders from the Global South brought dynamism and creativity to world missions that would foreshadow the seismic shifts taking place in global Christianity.

- Fuller Theological Seminary’s School of World Missions and the expanding Church Growth Movement brought a new dimension of sociological and anthropological research and quantitative analysis.

- Para-church ministries present were often founded and/or led by visionary activists and entrepreneurs whose growing influence and ability to raise money signaled a shift of influence from established denominational channels.

- Graham and the global influence of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) represented the seventh stream.

Graham brought the evangelical world together in Lausanne. The streams that found confluence in Lausanne gave it force and depth.

These same forces also created crosscurrents and carved new channels, creating movements within a movement:

- Many leaders from the majority world who identified with the need for holistic ministry formed the International Fellowship of Evangelical Mission Theologians (INFEMIT).

- Those who identified with the Fuller School of World Missions and the Church Growth Movement formed the AD 2000 Movement.

- The WEF leadership responded to the emergence of a new global movement through the development of a WEF Missions Commission.

Graham himself was ambivalent about the nature of the movement and chose to keep his singular emphasis on evangelism. He put his energy on future global gatherings into the Amsterdam conferences for itinerant evangelists. Para-church leaders frequently shifted their engagement from Lausanne to Amsterdam to AD 2000 and its various iterations. However, leaders of the student movements, particularly IFES, along with evangelically minded leaders within established churches, found resonance with Lausanne and provided a stability of service and leadership for it.

A legacy of theological reflection

The Lausanne Movement entered into a less visible and dynamic state following Manila. Much of the energy at the end of the second millennium was captured by enthusiasm for completing the task by the year 2000. However, the ambitious goals were not realized. The preoccupation with pragmatism and quantifiable results provided awareness of the need for more comprehensive theological reflection.

At the onset of the 21th century, conditions were disposed toward the vision and values of The Lausanne Movement with its commitment to serious biblical study and profound theological reflection as the basis for strategic mission engagement. Lausanne advocates the conviction that all theological reflection must be missiologically expressed, and all mission action must be theologically grounded. The two are inseparable if mission is to be authentic.

Lausanne ’74 represented the naissance of The Lausanne Movement. Cape Town2010 symbolized its renaissance: 4,200 participants from 198 countries, now related to 12 regional expressions and 36 issue networks, all committed to the foundational vision.

Such is the legacy of a congress convened forty years ago. No global congress before or since has had the depth of impact or the breadth of influence of this historic gathering. This is a gift from God through the magnanimous spirit of people like Graham and Stott.

Passing it on

It is therefore imperative that the spirit of and knowledge of Lausanne be passed on to the next generation. Indeed those who will best guide us into the future are those with the most comprehensive understanding of the past.

Exceptional curricular resources have been developed by Lausanne leaders over the last forty years. These are designed for use in local churches, colleges, and seminaries, and for personal study:

- Materials developed for study of The Cape Town Commitment are noteworthy, particularly those developed for seminaries by Dr. Darrell Bock and those written for churches by Rev. Dr. Matt Ristuccia and Rev. Dr. Sara Singleton.

- The Lausanne Occasional Papers provide wisdom from some of the church’s best minds on some of our most intractable challenges.

Just as Graham and leaders of his generation learned from and drew inspiration from the Edinburgh Conference, I trust that the next generation will be informed and inspired by what happened forty years ago at Lausanne ’74.

Endnotes

- Dr. David Bruce, Billy Graham’s personal assistant, in a phone discussion in August 2006 shared this conversation with the author.