In November 2014, General Jerome Kakwavu was convicted of war crimes including rape, murder, and torture. The case marked a breakthrough in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), being the first successful prosecution of a high-ranking officer for rape.

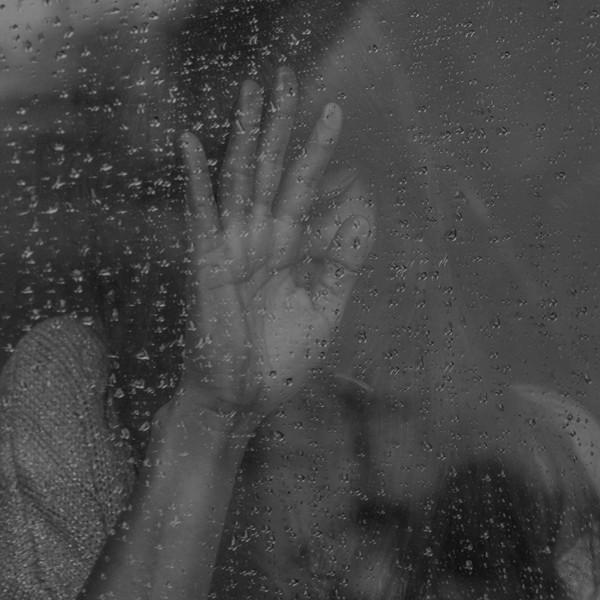

Yet in 2012, it was estimated that 1.8 million women and girls in DRC have been raped, many by government forces and armed militias. Some are babies or the elderly. The use of sexual violence (SV) has become a specific tactic in modern conflict: wars are being fought using women’s bodies as battlegrounds.

Undermining communities

The changing nature of armed conflict means that most casualties in modern conflicts are civilians. The days of a defined battlefield are gone. Access to civilians provides a direct means of undermining whole communities: once violated, women and girls are dead, injured, scattered, traumatised. Some may go on to bear their attackers’ children, or live with HIV. Added to this are cultural notions of shame and honour, meaning women can be permanently ostracised. If survivors flee, they are even more vulnerable as refugees.

When this happens to all the women and girls in a community, its male combatants are significantly weakened, morale and family life both devastated. If it becomes the norm in a country, entire populations are brutalised, leading to increasing perpetration by civilians too: even the ‘good guys’ become the ‘bad guys’. It significantly destabilises a region and makes post-conflict recovery far harder.

History

Records of the use of SV in war stretch back millennia. Rogue soldiers have long faced prosecution for SV (at least on paper), but its intentional and strategic mass use, commanded by senior officers, has only recently begun to be recognised by the international community.

International response

When the world’s media exposed the mass rape of women—and some men—in the 1990s Balkans conflict, prosecutions started moving forward as part of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. However, of an estimated 50,000 rapes, there were just over 60 successful prosecutions.

Since then, both the perpetration and legal framing of SV has been under intense scrutiny, most notably in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, South Sudan, and DRC. It has been the subject of the 2008 UN Resolution 1820, and the UN Secretary General has appointed a Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Why then the high levels of impunity, especially among those responsible for ordering the atrocities?

Geneva Conventions shortcomings

While national laws vary widely, the basic legal frameworks in international law concerning war are increasingly dated. Rape is mentioned in all the major documents, but these were laws written primarily about combatants, not civilians, and where SV is mentioned, it is framed as the (male) authors perceived it, not how women experience it.

The Fourth Geneva Convention, focusing on civilians, states: ‘Women shall be especially protected against any attack on their honour, in particular against rape, enforced prostitution, or any form of indecent assault’ (Article 27).

Note the wording: attacks ‘on their honour’ (in other articles, ‘outrages against personal dignity’), belying the horrific violence, akin to torture, that women actually experience. It also implies that, if a woman’s ‘honour’ has been attacked, there is stigma attached to being a victim.

Where the Geneva Conventions prohibit violence to life and person, cruel treatment and torture, and humiliating and degrading treatment, it is not made explicit that SV will fall within these categories. It has thus traditionally been viewed as less serious: what men experience in war is torture; what women experience is an attack on their honour. Bringing prosecutions in this context, in the chaos of a post-conflict society, means that SV has often been downgraded or overlooked.

2013 Declaration

One of the measures in the G8 2013 Declaration on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, led by UK Foreign Secretary William Hague and UN Special Envoy Angelina Jolie, rectifies this by specifically mentioning rape as a ‘grave breach’ of the Geneva Conventions. Significantly, any grave breach obliges all signatories to the Conventions to pursue those who have committed the crimes (or ordered them to be committed) and indict them.

This requires no UN Security Council or International Criminal Court involvement, theoretically speeding up the process and providing imperative. It means that potentially an aid or mission worker could report rape of civilians in conflict zones to their own government, which would be compelled to investigate.

Unfortunately, ‘grave breaches’ are only applicable in conflict zones: many refugee camps fall outside these areas.

Obstacles to justice

Broader definitions used in international law are stronger in prohibiting rape. Statutes and documents including the International Criminal Court Statute define all forms of SV as a crime against humanity, emphasising its seriousness. However, the burden of proof for a crime against humanity is extremely high, making it more difficult to prosecute.

Added to this is the way that SV in general, and rape in particular, has been defined. Early cases tried to establish lack of individual consent, rather than focusing more appropriately on the use of group force.

The practicalities of bringing prosecutions also face huge obstacles. Evidence is hard to gather. Witnesses and survivors usually have little access to justice structures: distance, poverty, and lack of knowledge are all factors. Many are terrified and ashamed, and face further threats from perpetrators and even families desperate not to have this ‘shame’ exposed.

Others have life-limiting injuries or illnesses such as HIV/AIDS as a result of their attack, restricting their ability to testify and constraining the time they have left—justice is a slow process. Post-conflict societies have deeply broken infrastructure, and in the chaos of rebuilding and potential regime change, seeking justice for a crime not seen as important can be almost impossible.

Recent progress

Despite these seeming difficulties, headway has been made in prosecutions over the past few years. They are still few and far between, but they are a start. Cases in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda blazed a trail by prosecuting rape as torture (already a grave breach) and even as genocide (on the basis that its use sought to destroy entire communities or change the ethnic makeup of children born as a result of rape).

They recognised too that men could be victims of SV: important in seeking justice for unrecognised male victims and also in changing the perception that this is ‘just a women’s issue’. How witnesses are treated and the political will to push the issue have also seen progress: in March this year, military commanders in DRC signed a declaration aimed at ending the use of SV.[1]

For many thousands of victims this still makes no difference, but it is important to keep a broader view and be encouraged by what is being done. It is easy to question the point of these laws if they are so difficult to implement, but without them there is no hope of justice at all. There are no overnight solutions, but legal frameworks are a starting point for ending impunity. Twenty-five years ago this issue was not even on the agenda of international security and peacekeeping discussions: things are moving forward.

Caring for survivors

Progress has also been made in treating survivors, although their lives will never be the same again. For many, they are too far away, too injured, too ashamed to seek medical help. However, for those who can, places such as survivors’ refuges and the Panzi hospital[2] in Bukavu, run by Dr Denis Mukwege, are a lifeline.

In countries like DRC, much of the work with survivors and their communities is done by faith leaders and organisations. Agencies such as UNAIDS have recognised faith organisations as the doorway to reaching communities at risk, particularly in remote regions.

Faith organisations’ role

As just one example, the Anglican Church of Congo has set up holistic trauma ministries, providing love, food, medical care, counselling, and skills training to those affected by the war, including SV survivors, ex-combatants, and children born of rape. They are working with Flame International on a ten-year programme to train all their leaders in supporting rape survivors.

The role of peacemaking is crucial: Rev Bisoke Balikenga, Provincial Youth Worker for the Anglican Church of Congo, says: ‘It is the problem of having conflict which let many people to create violence and others are raping because of not liking others. The Church is really helping by reconciling people and tribes.’

Rev Désiré Mukanirwa Kadorho, Development Coordinator and Vicar of Goma, eastern DRC, adds: ‘Church leaders had taken actions and look for solutions for putting an end on sexual violence and war and conflicts. The church work hand in hand with people involved in human rights and whoever is caught needs to be in jail and be sanctioned according to the law.’

What can the global church do?

Will we ever stop the use of SV in conflict? Probably not. However, we can vastly reduce its strategic use and the impunity of perpetrators. It is vital not to look only to national and international governmental bodies to tackle this.

The issue is not as far from our reach as it might appear. As stories of the use of SV increasingly emerge from Syria and Iraq, what can the global church do? In Rev Désiré’s words, ‘The [local] church cannot only stand [alone] on preventing [future problems] herself; it needs inputs and contribution of all stakeholders [and] from other people at international level.’

Faith institutions are the largest civil society organisations globally: we have more influence than we sometimes realise. These are just a few Christian organisations working on the issue of SV in conflict:

- Heal Africa[3] provides holistic medical care and social support to SV survivors in DRC. Its Make An Impact page has ideas on how to get involved.

- Flame International[4] is a UK-based charity that takes teams of volunteers into war-torn and suffering communities with God’s love and compassion for the broken. Its Participate page will tell you how to join them in making a difference.

- We Will Speak Out[5] is a faith-based coalition which works to end SV globally. See if there is a national coalition in your country, or look through their resources to see what you can do.

Raising the profile of this issue is vital. Hague and Jolie have brought it to the increased attention of the UN, national governments, and the general public, pushing for further implementation of existing measures to tackle the problem, in prevention, protection, and prosecution.

However, one does not have to be a celebrity or politician to have influence. Every citizen who has a vote has a voice, and as we collectively raise the profile of this problem, we influence our governments to act:

- Write to your government representative. Even better, get a group together to do so.

- Start work locally: SV is a problem confronting churches globally, despite being a taboo subject; so work to make sure your own church is a safe place for survivors and the vulnerable. This article has covered the use of SV in war, but that is only ever a continuation of SV and oppressive attitudes towards women in peacetime. As a church, we have a responsibility to influence these cultural norms.

It is about more than just handing over some money to others who are working on this, although that is helpful. It is about truly engaging with the issue and the people it affects.