In a sense the converted Jew is the only normal human being in the world. To him, in the first instance, the promises were made, and he has availed himself of them. He calls Abraham his father by hereditary rights as well as by divine courtesy. He has taken the whole syllabus in order, as it was set; eaten the dinner according to the menu. Everyone else is, from one point of view, a special case dealt with under emergency regulations.[1]

What we continually press upon Jews is that we believe Jesus is the Son of Man and Son of God, not in spite of, but because we are Jews. We believe that Jesus is the King of our people, the sum and substance of our Scripture, the fulfiller of our law and Prophets, the embodiment of the promises of our covenant. Our Testimony is that of Jews to Jews.[2]

Survey

From June 1-December 1, 2013, I spearheaded a broad study of Messianic Jews in North America as a follow-up to a similar study done in 1983. The 2013 study involved a sample of 1,567 respondents and, like its predecessor, sought to give a picture of the evolving Messianic movement for the purpose of resourcing that community as well as the greater missions community. In addition, my hope was to stimulate strategies for outreach, fellowship, and edification.

The quantitative questions I posed to the participants covered age, family background, education, religious observance, and vocation. The qualitative questions covered experiences in personal journeys and the impact of their faith decisions in relation to friends, families, and communities of this group. Anthropological categories emerged from this study which have given meaning to these experiences in their modern social and cultural setting. Most Jewish people today continue to resist the message of Jesus. My qualitative research attempted to understand this resistance in relation to the hardening of Israel (Rom 11:25).

Hardening

Paul understands this phenomenon as a warning (verse 25a), a mystery (v 25b), partial (v 25c), and temporary (v 25d, 26a). Part of my research attempts to understand hardening as a genuine and current experience, and I was able to demonstrate that hardening is interlaced into what I call an Implied Social Contract (ISC). I first heard this term in 1983 from the founder of Jews for Jesus, Moishe Rosen.

This type of contract is an agreement among a group of people that is never explicitly articulated. In other words, certain behavior is implied as normative; yet there is no formal law governing such norms. My research showed how this ISC is a way to understand and frame contemporary reflections on Jewish culture and the ways in which the Jewish community has found unity in its resistance to the Gospel. Understanding the conversation of the ISC shows an unspoken norm within Jewish culture.

Survival

That ethnic Israel has survived seems to be related to this phenomenon. Hardening serves a bewildering purpose: not only does it keep my people away from the Gospel; it also assists as a protection and preservation mechanism. The full research has been published in the journal Mishkan.[3]

The Jewish philosopher Simon Rawidowicz argues that Jewish survival is always under threat. In his essay ‘Israel: The Ever Dying People’, he articulates that Jewish survival is so acute that the life of the Jewish people is a perpetual quest to control their future.[4] This historical reality seems unparalleled in history. The Jewish people seemed destined to disappear. They have been exiled and exterminated in dozens of lands. Yet as Jewish people seem to be ever dying, they continue to live and prosper. Self-preservation, he argues, has become the prime value of Jewish culture. Hardening is related to this impulse.

Highlights of the quantitative analysis

- Most people had heard the Gospel by the time they were 25.

- The median age for first hearing the Gospel is 17 and for responding in faith is 22.

- The most common way that respondents heard the Gospel was through personal conversation.

- Those who respond find truth that is consistent and coherent with Scripture.

- Most of our respondents sometimes feel like strangers inside the majority Jewish culture.

- Respondents are still socially integrated into the wider cultures they live in.

- The Messianic Jewish community in North America is more similar to the American Jewish community than to the general US population in demographics such as Jewish dispositions (ie the tendency to act in certain ways that are learned in the culture), education, and occupation.

- Lifestyles, values, and identities of most of our respondents continue to show efforts to maintain a connection to Jewish tradition, on the one hand, and choice on the other. The results showed a broad consensus that reflected a commitment to Jewish character, culture, and continuity.

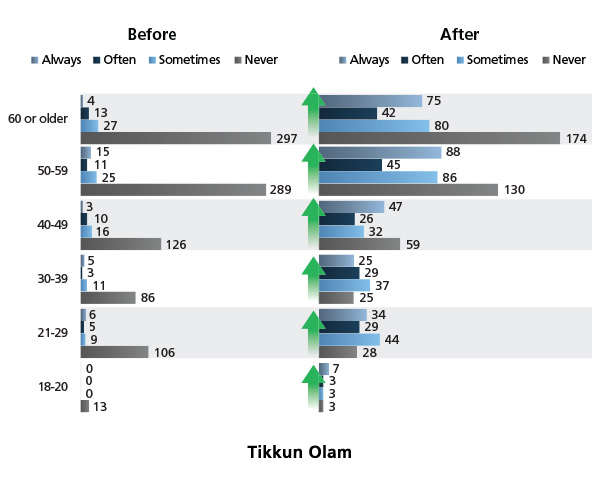

- With regard to the Jewish value of tikkun olam (repair of the world) and without providing specifics, we see a very significant increase in orientation across age groups toward this practice after coming to faith. The increase here was the most notable among all the values examined. The chart below shows how these values play out. Of all the Jewish values examined, this showed the most startling renewal.

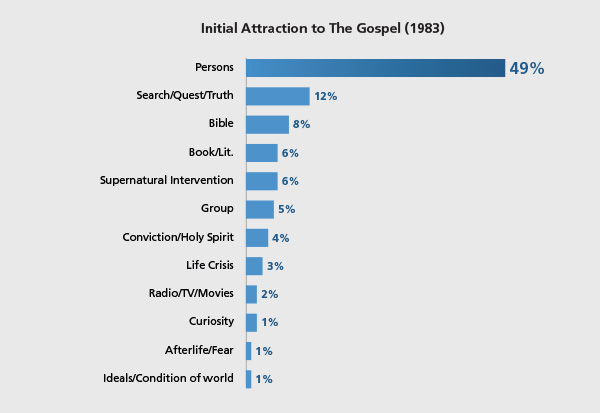

Other interesting results are illustrated below. I compare how Jewish people are hearing the Gospel in 1983 and 2013. The questions were framed differently, but the pattern suggests that most Jewish people are hearing the Gospel in the marketplace. There is an increasing influence of churches and Messianic congregations:

Qualitative highlights

In the September 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, my colleague Susan Perlman wrote about scaling adversity.[5] My research here is related to this significant topic. My qualitative questions covered experiences in personal journeys and the impact of their faith decisions in relation to the friends, families, and communities of this group.

Many respondents experienced adversity. They called it many things: social control, guilt, shame, hardening, and loss of prestige. Today Jewish people in North America are continuing to experience adversity as they hear and respond to the Gospel.

Respondents were asked to characterize this adversity in their experience:

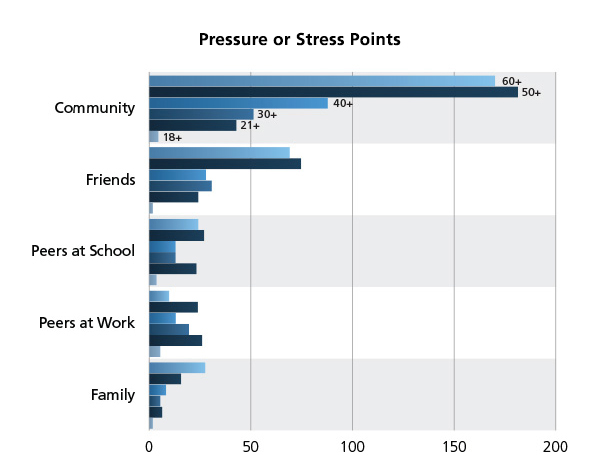

- The major pressure points involved what it would mean for relationships in the Jewish community.

- Infidelity to the Jewish community was especially a point of pressure for the 50+ group.

- Pressure points, especially regarding community, factored less significantly among younger generations.

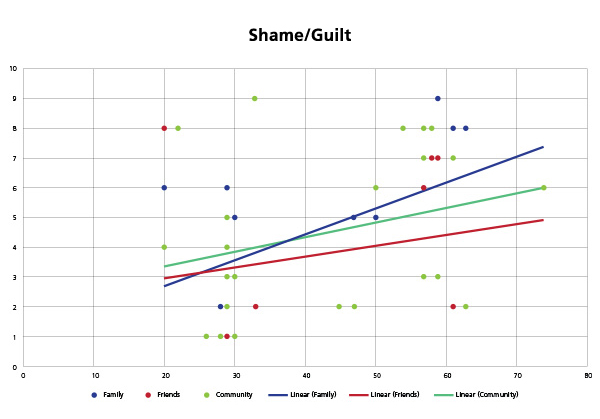

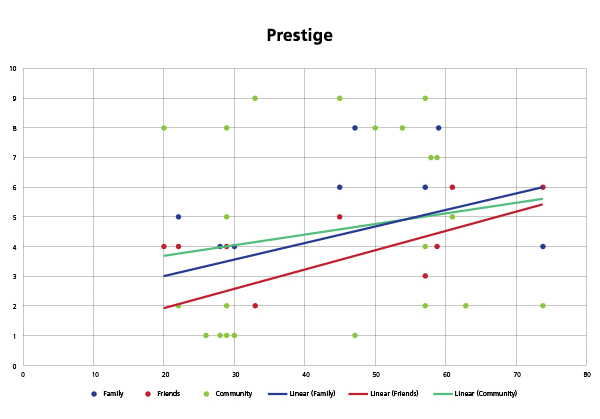

Below are two charts outlining the sources and types of pressure. We can see that the older groups experienced more adversity than the younger groups. The graphs represent those who noted that they experienced this kind of adversity in a particular age group.

As I interviewed this group, several subjects manifested around social control, such as prestige, shame and guilt, and hardening.

I asked if they could articulate what hardening was or how it manifested itself in their experience. Common answers were ‘death’; ‘loss’; ‘apathy’; ‘identity separation’; ‘tribal’; ‘when I was in the synagogue I was the Christian. When I was in the church I was the Jew’; and ‘hardening is seen in both directions’.

Of the 24 people in the group, two were disowned; two experienced religious control; three lost job opportunities; three were uninvited to family/community events; and five experienced psychological control—‘You cause us pain. You are hurting your grandparents. You will not be able to marry a Jew. You are a Gentile.’

I was interested in fleshing out some of these categories. I asked the group to try and measure these various points of adversity with regard to the themes that were emerging. Below are the results of Shame and Guilt and Loss of Prestige.

I asked them to ‘measure’ on a scale of 1-10 the intensity of this kind of adversity. These were done in relation to friends, family, and community. The scatter graphs are below along with the trend analysis. You can see a diversity of experiences across age groups with similar trends across the age groups.

Next steps in this research will include improving the quality of the survey; asking new questions with regard to social media; and surveying all the Messianic communities outside of North America.

Broader global missiological concerns

Issues surrounding Cultural Guidelines and Social Control are familiar to anyone involved in cross-cultural missions. The particular issues I face in Jewish mission resemble common phenomena that vary from society to society. Loss of categories, secularism, and urbanization are changing the way younger generations are experiencing social control. I believe that the concerns which flow from my research are foundational to global mission concerns:

- A vigorous ongoing conversation is needed about the extent to which we need to prophetically challenge people while remaining part of the communities in which we minister.

- We must respect the influence of indigenous congregations.

- We need to build relationships, make the Bible available, plan for, and address adversity.

- We must talk to people we disagree with so that we can refine our positions.

- We must challenge and be challenged by the status quo in communications and methodology. I believe that God enjoys human creativity and we should be open to all the new platforms that technology provides.

- We must be honest in communicating failures to our donors. It is easy to hit the side of a barn door and draw a circle around it and tell the world that you made a bull’s-eye.

- As we evaluate our current and potential platforms, we must avoid communication that is syrupy, far-fetched, and irrelevant. Meaning must be provided into the social context of those whom we intend to reach.

- We must not assume that people will cross over social and cultural boundaries to listen to us.

- We must apply appropriate speech and categories. I do not propose a new tactic, but an old tactic applied in a new way—receptor-oriented communication.

Furthermore, we must not be afraid to ask these questions:

- Is our material relevant to the group receiving the message rather than those bringing it? Is our material bound by our culture or designed for the people and paradigms of the societies we are speaking to?

- Are we talking to the people we should be talking to?

- Do we have the courage to face hardship and opposition?

- Are we willing to exercise critical judgment regarding material, methods, and projects used? Do they work now? Can we assess and/or measure?

Conclusion

Appropriate and relevant speech affirms the dignity of all people. Communication must be tied to the consciousness of the hearers. This principle is at the heart of contextual ministry.

Endnotes

- C S Lewis, Introduction to Smoke on the Mountain: An Interpretation of the Ten Commandments by Joy Davidman (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1953), 7.

- David Baron, The Ancient Scriptures and the Modern Jew (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1900), 337.

- Andrew Barron and Bev Jamison, ‘A Profile of North American Messianic Jews’, Mishkan 73 (Jerusalem: Caspari Center for Biblical and Jewish Studies, 2015).

- Simon Rawidowicz, ‘Israel: The Ever Dying People’, Studies in Jewish Thought, N N Glatzer, ed, (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1974), 210-214, 220.

- Read the full article at https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-09/scaling-adversity.