The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.—M K Gandhi

Violence against minorities in India

In spite of a rich tradition and legal framework supportive of freedom of conscience and the right to practise, profess, and propagate the religion of one’s choice, religious minorities in India find themselves frequent victims of religiously motivated violence.

According to human rights groups, in 2015 there were over 160 incidents where Christians were targeted for their faith, with the highest number of incidents coming from Madhya Pradesh, followed by Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. The cases included physical assaults and threats and intimidation. In some instances, women reported being sexually assaulted and threatened.[1]

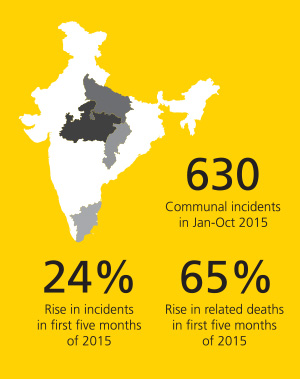

According to the Ministry of Home Affairs, there were over 630 communal incidents in January-October 2015. Communal violence in India registered a rise in incidents by 24%, and related deaths by 65%, in the first five months of 2015.[2]

In its annual report for 2015, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) noted that since the 2014 general elections in India, religious minority communities have been subject to ‘derogatory comments by politicians linked to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’ and ‘numerous violent attacks and forced conversions by Hindu nationalist groups’ such as Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP).[3]

Allegations of religious conversions

One of the primary causes of violence against the minority Christian population is the making of allegations of conversions by force and allurement. In a recent case,[4] members of the Bajrang Dal, a Hindu extremist organisation, caught hold of a pastor and paraded him on a donkey in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh with his head half shaven. They alleged that the pastor converted a man without his consent. Similarly, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, police arrested 13 people, including a blind couple, on January 14, 2016, for allegedly trying to convert a few residents by offering inducements or using force.[5]

While there are numerous such incidents that come to light each year, there is very little evidence to show that Christians have engaged in coercive practices to gain new converts. Asma Jahangir, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, noted in her report on India in 2011 that:

‘Even in the Indian states which have adopted laws on religious conversion there seem to be only few—if any—convictions for conversion by the use of force, inducement, or fraudulent means. In Orissa, for example, not a single infringement over the past ten years of the Orissa Freedom of Religion Act 1967 could be cited or adduced by district officials and senior officials in the State Secretariat.’[6]

In spite of the absence of credible data to support laws restricting religious conversions in India, there are voices within the government which have called for a national law.[7] In April 2015, Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh of the BJP called[8] for a national level anti-conversion law in response to reports of coercive reconversions to Hinduism and various attacks against members of religious communities.[9]

Legal restrictions

Similar laws have been enacted at the state or province level in Odisha (previously known as Orissa) in 1967, Madhya Pradesh (1968), Arunachal Pradesh (1978), Gujarat (2003), and Himachal Pradesh (2006). Euphemistically titled ‘Freedom of Religion Act’, they are commonly known as anti-conversions laws:

- In 2002, the Tamil Nadu state assembly passed the Prohibition of Forcible Conversion of Religion Bill, which was repealed in 2004 after the defeat of the BJP-led coalition.

- In 2006, the BJP-led government in Rajasthan passed a similar freedom of religion bill. However, assent of the President of India is still pending ten years after the bill was forwarded to him.

- The BJP in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh also unsuccessfully sought to tighten existing laws the same year.

Basic features of the laws

These laws are very similar in content, and claim to prohibit conversions by force, fraud, and inducement or allurement. The Acts state that no person shall convert or attempt to convert, either directly or otherwise, any person from one religious faith to another by the use of force or by inducement or by any fraudulent means, nor shall any person abet any such conversion.

Punishments

The Acts carry penal provisions and punishments, generally ranging from up to a one-year imprisonment and a fine of up to 5,000 Indian rupees to up to three years imprisonment and a fine of up to 25,000 Indian rupees. The punishment is more stringent if there is evidence of conversion by force, fraud, or inducement among women, minors, and Dalits (formerly ‘untouchables’ as per India’s caste system), or Tribals. Failure to send notice to or seek permission from the district magistrate before converting or participating in a conversion ceremony also renders one liable for a fine under the Acts.

Effect of the laws

Reports from the various minority communities and human rights agencies reveal that these laws foster hostility against religious minority communities. In several states, prosecutions have been launched under the Freedom of Religion Acts against members of the minority Christian community. There have also been frequent attacks against the community by members of right-wing Hindu groups on the pretext of ‘forcible’ conversions.[10]

South Asia

In spite of the effect of these provisions, Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar have also enacted similar laws, with Nepal going so far as to include them in the recently adopted constitution. A similar proposal was introduced in Sri Lanka, but was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2004.[11]

Nepal

Article 26 of the Constitution of Nepal, 2015 (2072), protects freedom of religion, stating: ‘(1) Each person shall be free to profess, practice, and preserve his/her religion according to his/her faith.’

However, section 26(3) of the constitution states that ‘no person shall act or make others act in a manner which is contrary to public health, decency, and morality, or behave or act or make others act to disturb public law and order situation, or convert a person of one religion to another religion, or disturb the religion of other people. Such an act shall be punishable by law.’

The General Code in Chapter 19 which deals with Decency/Etiquette (‘Adal’) states in Number 1.512:

‘No one shall propagate any religion in such manner as to undermine the religion of other nor shall cause other to convert his or her religion. If a person attempts to do such act, the person shall be liable to imprisonment for a term of Three years, and if a person has already caused the conversion of other’s religion, the person shall be liable to imprisonment for a term of Six years, and if such person is a foreign national, he or she shall also be deported from Nepal after the service of punishment by him or her.’

Bhutan

The Constitution of Bhutan in Article 7:4 states: ‘A Bhutanese citizen shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. No person shall be compelled to belong to another faith by means of coercion or inducement.’

In furtherance to this provision, in 2011, the legislature amended the Penal Code. The newly introduced Section 463 (A) states that: ‘A defendant shall be guilty of the offense of compelling others to belong to another faith if the defendant uses coercion or other forms of inducement to cause the conversion of a person from one religion or faith to another.’

Section 5 (g) of the Religious Organizations Act of 2007 also states that ‘no Religious organizations shall compel any person to belong to another faith, by providing reward or inducement for a person to belong to another faith.’

Myanmar

The unofficial translation by the Chin Human Rights Organization of the Religious Conversion Law states:

’14. No one is allowed to apply for conversion to a new religion with the intent of insulting, degrading, destroying, or misusing any religion.

15. No one shall compel a person to change his/her religion through bonded debt, inducement, intimidation, undue influence, or pressure.’

The law also requires that the person wishing to convert should give the local authorities intimation of his/her conversion so that they can conduct an inquiry into it. The prospective converts would also be required to undertake special classes to understand the tenets of the religion.[12]

Pakistan

While Pakistan does not have anti-conversion laws, laws pertaining to blasphemy have a very similar effect on persons converting to religions other than Islam.[13]

Conclusion

A detailed analysis of these laws reveals that, far from promoting or protecting religious freedom, they have served to undermine the religious freedom guarantees under the Indian constitution and international law and the covenants to which India is a signatory.

Primarily motivated by a religious ideology, the anti-conversions laws fail to achieve the very purpose for which they have been enacted. On the contrary, they provide an opportunity for divisive forces to target the constitutionally protected rights of minority groups and pose a serious threat to the free practice and propagation of religious beliefs.

Furthermore, the laws fail to account for the agency of converts and treat them instead as passive recipients of external (and seemingly unwanted) pressures from ‘predatory’ convertors. They tend to treat all religious conversions as suspect and liable to investigation and prosecution.

The introduction of similar provisions in the other South Asian legal systems is a disturbing trend and requires the attention of the international community, as they stand in direct contrast to the rights and liberties guaranteed under international law.

This unchecked spreading of anti-conversions laws will affect the safety and security of local Christians wherever it occurs, as has been in the case in India.

Endnotes

- Data collated fromcowever, section 26(3) of the CC www.SpeakOutAgainstHate.Org.

- http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Communal-violence-shows-24-jump-in-first-five-months-of-2015-shows-govt-data/articleshow/48167102.cms

- http://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/India%202015.pdf

- http://www.christiantoday.co.in/article/pastor.humiliated.paraded.head.half.shaven.on.donkey.on.false.conversion.charges.in.u.p/17834.htm

- http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/blind-couple-among-13-in-madhya-pradesh-held-for-conversion/

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Asma Jahangir : addendum : mission to India, 26 January 2009, A/HRC/10/8/Add.3, http://www.refworld.org/docid/498ae8032.html, accessed 12 April 2016.

- http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/forcible-conversions-religion-narendra-modi-ghar-wapsi/1/407628.html

- http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/states-should-act-against-communal-incidents-rajnath/article7150757.ece

- https://www.sikh24.com/2015/11/05/indian-parliament-will-consider-criminalizing-religious-liberty/#.VrHoUk3UiUk

- Taking note of this trend, in its 2011 report, the USCIRF noted that: ‘The harassment and violence against religious minorities appears to be more pronounced in states that have adopted “Freedom of Religion” Acts or are considering such laws.’ The report further stated that: ‘These laws have led to few arrests and reportedly no convictions.’ According to the US State Department, between June 2009 and December 2010, approximately 27 arrests were made in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, but resulted in no convictions.

- http://www.csw.org.uk/2004/08/23/press/366/article.htm

- https://www.mnnonline.org/news/anti-conversion-laws-in-burma-a-nail-in-religious-freedoms-coffin/

- http://www.npr.org/2012/11/20/165485239/blasphemy-charges-on-the-rise-in-pakistan