Her only fault was that she was born in the wrong part of town. Because of the district in Japan where Kyoko (not her real name) came from, she was considered a ‘burakumin’, one of the ‘untouchables’. Hundreds of years ago, these districts were home to leatherworkers, tanners, gravediggers, and other professions considered unclean to Japanese society. Even today, people from the outcast areas can suffer discrimination in their search for jobs, housing, and marriage partners. It is not uncommon for parents to use private investigators to check out the background of their children’s intended partners, and for matches to be called off if a buraku link is discovered.

Kyoko learnt to think of herself as below those around her. She made friends with other burakumin, but she was always careful around people she did not know. She did not feel like she really fit in; everywhere she went she carried a sense of shame.

When Kyoko first heard about God, she wondered why God had made her a burakumin. However, as she learnt about how Jesus ‘emptied himself’ and ‘became nothing’, she came to believe in a God who loved buraku and non-buraku Japanese equally. She has been set free from her shame.

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

by Jon Ronson

Online shaming

Kyoko’s experience is, of course, not unique to Japan. After I left Japan and moved to Australia, I realised that similar dynamics of shame, humiliation, and rejection are everywhere. Jon Ronson, who wrote a book entitled, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, about the phenomenon of online shaming, believes that we are ‘at the start of a great renaissance of public shaming’[1]:

Ronson gives the examples of Justine Sacco, the American PR executive who was publicly derided on the Internet after an ill-advised joke which ‘ruined her life’[2], and Adria Richards, who faced a public backlash after shaming two computer developers behaving inappropriately at a conference.

Here in Australia, one Melbourne man found his ‘name smeared’ after a false accusation about him was shared thousands of times on Facebook.

Social media have given everyone a megaphone, and reputations can be destroyed in seconds with a viral tweet. As a result, we are all becoming more sensitive to shame and its power.

Social media have given everyone a megaphone, and reputations can be destroyed in seconds with a viral tweet. As a result, we are all becoming more sensitive to shame and its power[3].

Typical reactions to shame

Roberto (again, not his real name) moved to Australia from South America twelve years ago. He speaks reasonable English with a strong Hispanic accent, although his children sound just like their Australian friends. Some time ago he suffered racist abuse from co-workers at the school where he worked, and not long after reporting it to the management and going through a process of arbitration, he found himself terminated and is now unemployed. He feels ashamed of his language, his inability to provide for his family, and the isolation he has endured as a foreigner.

Some friends tried to share the gospel with him, but the idea of God taking away his sin did not resonate at all—he sees himself not as a sinner, but as sinned against! What is the gospel for Roberto?

If we are shamed by our society, then we remove ourselves from society.

Let us first listen to what Roberto and Kyoko said about their situations. ‘I felt like I wanted to disappear’. ‘I just want to stay in the house and never go out’. ‘I felt like it would be better if I had not been born’. These, according to psychologist Michael Lewis, are classic reactions to the feeling of shame and humiliation. When we feel ashamed, we want to run away, to hide, to put a distance between ourselves and the situation or people that shamed us. We cannot remove the shame from ourselves; so we remove ourselves from the source of the shame. If we are shamed by our society, then we remove ourselves from society.

Günter Seidler describes the experience of shame as the desire ‘to remain invisible or in extreme cases to be extinguished’[4]. Figuratively speaking, we drive the shameful person into non-existence; we put the person who was shamed to death. Ronson writes about how the victims of Internet shaming talk about themselves as being ‘destroyed’, ‘annihilated’ and ‘killed’[5].

20-30K

Japanese people end

their lives every year

In some countries, this is more than just a metaphor. In Japan, an individual who is shamed or humiliated will often remove himself from society through self-imposed ostracism or even suicide. Around 20,000 – 30,000 Japanese people choose to end their own lives every year. The reasons are naturally varied, and Japan’s relative lack of access to mental health services means that clinical depression is not dealt with in the same way as in the West. However, among the complex web of reasons for suicide, financial and job-related worries seem to be most common. Financial failure or loss of employment, leading to a feeling of being unable to provide for one’s family, brings a sense of shame that can be impossible to bear.

In the Middle East, too, the solution to shame is sometimes found through death. On 16 March 2008 in Iraq, Rand Abdel-Qader was stabbed to death by her own father. Her brothers helped to kill her and throw her into a pit, while her uncles stood around to spit on her corpse. She had brought shame on her family by talking with a British soldier, and the only way to restore the family’s honour was for her shameful body to be removed from society.

Baptism as death and rebirth

When we share a gospel of sin being forgiven and relationship being restored, we often assume that someone’s life just needs patching up a little. Jesus takes away your sin, and you go on living. However, if we look at the gospel that Paul preached, we find something far more radical: you have died. Your life up until this point is over. When you went down into the waters of baptism, you were united with Christ in his death. When you came up out of the water, you were united with Christ in his resurrection and given a new life and a new identity. Christ gives the shamed person exactly what they long for—the gift of death.

Baptism as death and rebirth is a powerful image for those whose old life carries the burden of shame. In fact, it always has been: between the second and fourth centuries, converts to Christianity were baptised naked. Cyril of Jerusalem explains the link between nakedness, baptism and the removal of shame:

As soon, therefore, as you enter in, you put off your garment; and this was an image of putting off the old man with his deeds. Having stripped yourselves, you were naked; in this also imitating Christ, who hung naked on the Cross, and by His nakedness spoiled principalities and powers, and openly triumphed over them on the tree. You were naked in the sight of all, and were not ashamed; for truly you bore the likeness of the first-formed Adam, who was naked in the garden and was not ashamed.[6]

The church as God’s solution

However, how does dying and being reborn spiritually help Roberto and Kyoko practically? Roberto is still unemployed. Kyoko is still a member of an outcast group.

The answer is that shame is a problem of community; it happens because I am deriving my identity from the people around me, just like Adam and Eve who took their eyes off their Maker and had their eyes opened to one another. Shame is only a problem for me because of the opinions of my peers, my in-group, and the people I care about. You might not be able to change the opinions, but you can certainly change the people: as well as putting the old self to death, baptism is also the gateway to a new community, the community of the people of God.

The gospel does not just change who we are, but it gives us a new society, a new family, and in our new family we are accepted without shame.

Norman Kraus, a former missionary to Japan, wrote that when dealing with shame, ‘the changed pattern of relationships is an essential part of the gospel of salvation itself’[7]. The gospel does not just change who we are, but it gives us a new society, a new family, and in our new family we are accepted without shame.

This is why it is so important for the people of God to avoid playing the shame game, and to relate to one another by God’s standards, not by the world’s. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians is full of warnings about the dangers of factionalism, judgment, and comparison in the Christian community. Instead, he replaces these things with the image of one body, working together, the weaker members indispensable, and the more shameful members treated with special honour.

We can see from this that the church itself has a key part to play in God’s solution for shame. Christ gives a brand new life to the person suffering from shame; the church gives them a brand new arena in which to live. When these two things come together, real freedom is possible.

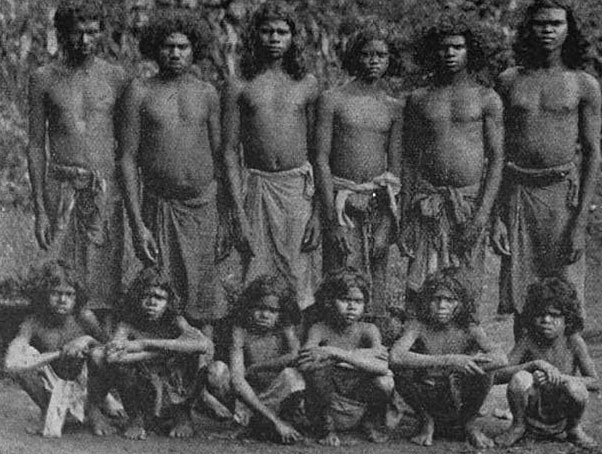

Kyoko has now become a missionary in India, where she helps another group of ‘untouchables’ to see that Jesus is not ashamed of them. Roberto is still not yet a Christian, but he has found a group of Christian men that he continues to journey with—men who do not see his employment status or immigration status, but see him as he really is, as a bearer of the image of God.

Untouchables of India, Malabar, Kerala (1906).

Endnotes

- J. Ronson, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (London: Picador, 2015), 9.

- Ibid., 69.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Jayson Georges entitled, ‘The Good News for Honor-Shame Cultures’, in the March 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis. https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-03/the-good-news-for-honor-shame-cultures.

- G. H. Seidler, G H, In Other’s Eyes: An Analysis of Shame (Madison, CT: International Universities Press, 2000), 207.

- Ronson, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, 175.

- Cyril of Jerusalem, Mystagogical Cathecisis II – On the Rites of Baptism, 59-60.

- C. N. Kraus, Jesus Christ Our Lord: Christology from a Disciple’s Perspective (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1990), 241.

Photo credits

Feature image from ‘THE “ETA 穢多”, “BURAKUMIN 部落民”, and “HININ 非人” – The Non-Human Outcasts of Old Japan‘ Source: Okinawa Soba (Rob) (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).