The historical pattern of expansion in mission resourcing has not been a process of even progress from a single center. The 20th century marked a change in the flow of missionary personnel and financial resources from the Western world to the non-Western or majority world, and from the Global North to the Global South. What are the realities of this transition? How can we understand its nature? What does this change imply for future intercultural ministries? These are important questions to ask as we envision and strategise future ministries.

Southward turn

The main theme of the 1938 International Missionary Council (IMC) conference in Tambaram was the ‘Upbuilding of the younger churches as a part of the historic universal Christian community’. The 1938 IMC foresaw the future of world Christianity resting with the younger churches.[1]

From Every People (1989)

by Larry D. Pate

Larry D. Pate’s book From Every People (1989) projected that by the year 2000, the majority of Protestant missionaries would be from the non-Western world, assuming the growth rate of the time continued.[2] His subsequent projection was that by 2000, there would be approximately 131,700 Western missionaries and 164,200 non-Western missionaries.[3]

However, Michael Jaffarian, in an article in 2004, pointed out that Pate counted both domestic and foreign missionaries for the non-Western world, while only counting foreign missionaries for the Western world.[4] His analysis of the 2001 Operation World data suggested that there were still more Western Protestant missionaries than those from the non-Western world:

- Jaffarian’s total count of non-Western missionaries reached 91,837—less than the 103,437 Western missionaries.[5]

- He also pointed out that the growth rate of non-Western Protestant missionaries was 210 percent for the period of 1990–2000, while the rate for Western missionaries was only 12 percent.[6]

My own observation is that Pate’s projection was not totally unsupported, even though he did not compare the same kind of missionaries. Pate focused on Protestant missionaries, whereas Jaffarian’s analysis showed the comparison including Roman Catholic missionaries. If we compare Protestant missionaries only, we could conclude that Pate’s projection was simply delayed in coming true. It could be that the number of non-Western Protestant missionaries outnumbered that of Western counterparts not by the year 2000, but by, say, 2010. To verify this hunch would demand solid empirical research.

Korean missionary movement

The missionary movement in Korea might not be a typical example of a majority world missions movement. Korea belongs to the non-Western world, but is also a part of the Global North, like a few other developed Asian countries. The categorisation can be different depending on whether the criterion is cultural or economic. What is important is that the Korean missionary movement provides an example of a former mission field turned into a sending base for missionaries.

93

Korean missionaries working in 26 countries through 21 mission agencies in 1979

21,220

Korean missionaries working in 159 countries through 159 mission agencies in 2017

This shift may look dramatic on the outside, but it took a lot of time and energy inwardly. The Korean church commissioned its first cross-cultural missionary Ki Poong Lee (1868–1942) to Jeju Island in 1907. It commissioned its first missionaries to go abroad in 1912 when Tae Ro Park, Young Hoon Kim, and Byung Soon Sah, set off for Shandong, China. After Korea’s independence, the Korean church sent more missionaries to other countries:

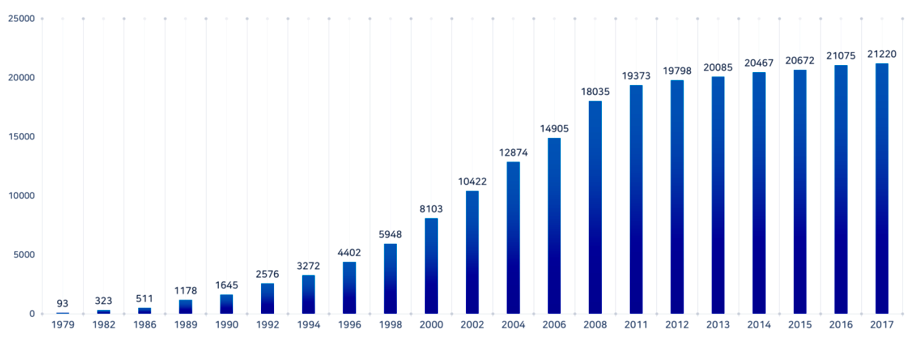

- According to Marlin L. Nelson’s pioneering research on Korean missionaries and mission agencies, there were 93 missionaries working in 26 countries through 21 mission agencies in 1979.[7]

- By the end of 2017, there were 21,220 Korean missionaries working in 159 countries through 159 mission agencies (Figure 1).[8]

The Korean church is now an important source of mission resourcing.

The Korean church is now an important source of mission resourcing. The churches in Korea today spend more than USD 363 million a year to support their missionaries’ ministries, counting only the amount that has been channeled through mission agencies and not including direct expenditures.[9]

The Number of Korean missionaries (1979-2017)

Figure 1.

It was in 1832, when Karl Friedrich August Gutzlaff (1803–1851) arrived in Korea for a short-term ministry as an itinerant, that Korea saw its first missionary. The first long-term missionaries Horace Grant Underwood (1859–1916) and Henry G. Appenzeller (1858–1902) did not arrive in Korea until 1885. Thus it did not take long before the Korean church began to send its own missionaries. However, it took almost 100 years for it to see a major missions movement catalysed to send multitudes of missionaries, with the start of the Mission Korea Student Convention in 1988.

Korea is only one example of the missions movement in the majority world. There are now multiple streams of the global missions movement in many parts of the world.

Polycentric expansion

The pattern of expansion in Christian missions is not a process of even progress emanating from one permanent center, like that of Islamic expansion.[10] After a number of serial expansions, there are now multiple centers in Christian missions.[11]

The dichotomy between Western world and majority world or Global North and Global South gives the impression of a dramatic or paradigmatic shift in mission resourcing. The reality, however, is much more complex than this simple description. Looking into the process of the changes enables a subtle understanding of the gradual and cumulative dynamics of change. There is much more continuity than the titles of Pate’s writings convey. The Western centers are still functioning as missionary-sending bases, although there are new centers expanding continually in the majority world.

The global missions movement is expanding through polycentric multiplication in this ever-globalising world.[12] The question is no longer a binary one of Western or non-Western. The issue is how to harness the plurality of the streams of the global missionary movement.

The Global South has as much or even more heterogeneity than the Global North. The cultural difference or distance between an Asian country and a Latin American country might be greater than those between an Asian country and a Western country. In this global age, categorising difference as a black and white dichotomy is no longer valid. The polycentric or pluralistic model is more realistic and applicable.

Missiological implications

We therefore need to pursue true globalism in doing theology and ministry, overcoming the dichotomic view of Western versus non-Western. There are many kinds of parochialism that we need to overcome. No localism should dominate the scene. We need to pursue a dynamic balance between the global and the local.

Incarnational ministry in this global age requires a deep commitment to a respectful mindset.

The art of leadership and competence in this diversifying world lies in how to handle differences.[13] These differences are a given reality in such a world; what is important is how to deal with them. A desirable attitude is to appreciate, celebrate, and maximise the benefits of the differences to make them positive dynamics for synergy. Ethnorelativism, rather than ethnocentrism, will provide a foundation for this kind of positive attitude toward differences. As we respect other perspectives, norms, and categories, we can creatively maximise the benefits of being different. Heterogeneity might be uncomfortable, but it is an important condition for a synergistic relationship.

Incarnational ministry in this global age requires a deep commitment to a respectful mindset. It is not just a matter of strategy, but an essential quality of missional spirituality and leadership. True identification with people from other cultural backgrounds starts with recognising the different realities. True ecumenism honestly recognises and accepts the essential differences and learns to coexist with them.

What might be the practical side of the missiological implications? I would propose three ‘I’s:

- Interacting with other localities. A true practice of missional globalism would emphasise more efforts to cross cultures and traditions and work together.

- Integrating diverse localism into a globalism. We need to prioritise a willingness to accept one another and learn to form common ground overcoming differences.

- Standing in between the global and local in doing theology and ministry. We need to build up cross-cultural competence to think and work in and above culture.

To be more concrete, we need to invite others from different cultural backgrounds more. If necessary, we need to lower our expectations of proficiency in communicating. We should ask more questions instead of positing ready-made arguments. An emic category in a culture or language may not exist or be relevant in another culture or language. Asking questions instead of assuming common ground is cross-cultural wisdom.

Asking questions instead of assuming common ground is cross-cultural wisdom.

Also, we should listen more carefully. Before embarking on a discussion or consensus building, we need to pay attention to what others have to say. Sometimes what others are saying between the lines is very important. Inviting, asking, and listening are basic yet significant practices comprising a global mindset.

I have greatly benefited from inviting mission leaders from other cultural backgrounds into our programs. It has been an important part of God’s blessing on my pilgrimage. More recently, I have gratefully enjoyed various invitations from other corners of the world to write (as with this article), speak or share, give feedback, brainstorm together, or sometimes just to chat. Overall, I have benefited more from the friendship and companionship than I have contributed to it.

Let us invite people from the other side of the world into our fellowship and meeting; let us ask them to give us their feedback, share their thoughts and feelings, and participate in dialogue towards our common agenda; and let us listen to them more carefully to build mutual understanding and opportunities for cooperation and collaboration.

Endnotes

- Dana L. Robert, ‘Shifting Southward: Global Christianity Since 1945’, International Bulletin of Missionary Research Vol. 24, No. 2 (New Haven: Overseas Ministries Study Center, 2000), 57.

- Larry D. Pate, From Every People: A Handbook of Two-Thirds World Missions with Directory/Histories/Analysis (Monrovia: MARC, 1989).

- Larry D. Pate, ‘The Changing Balance in Global Mission’, International Bulletin of Missionary Research Vol. 19, No. 2 (New Haven: Overseas Ministries Study Center, 1991), 59.

- Michael Jaffarian, ‘Are There More Non-Western Missionaries than Western Missionaries?’, International Bulletin of Missionary Research Vol. 28, No. 3 (New Haven: Overseas Ministries Study Center, 2004), 131.

- Ibid., 132.

- Ibid.; Enoch Wan, Michael Pocock eds. Missions from the Majority World: Progress, Challenges, and Case Studies. E-Book (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2009), Loc 168.

- Marlin L. Nelson, Directory of Korean Missionaries and Mission Societies (Seoul: Asian Center for Theological Studies and Mission, 1979), 43.

- Steve Sang-Cheol Moon, ‘Missions from Korea 2018: Mission Education’, International Bulletin of Mission Research Vol. 42, No. 2 (OMSC & SAGE, 2018), 171.

- Steve Sang-Cheol Moon, ‘Missions from Korea 2013: Microtrends and Finance’, International Bulletin of Missionary Research Vol. 37, No. 2 (New Haven: OMSC, 2013), 96-97.

- Andrew F. Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission and Appropriation of Faith (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2005), 13.

- Ibid., 13, 45.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Allen Yeh, entitled, ‘The Future of Mission is from Everywhere to Everywhere’, in January 2018 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2018-01/future-mission-everyone-everywhere.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Ben Thomas, entitled, ‘How Can We Finally Reach the Unreached?’, in March 2018 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2018-03/can-finally-reach-unreached.