Prefatory Note

This Lausanne Occasional Paper is a product of the Lausanne Consultation on Children at Risk, Quito, Ecuador, November 17–19, 2014

Writing/Editing Team:

Dr. Desiree Segura-April

Dr. Susan Hayes Greener

Dr. Dave Scott

Dr. Nicolas Panotto

Mrs. Menchit Wong

Preface

This Lausanne Occasional Paper is a product of the Lausanne Consultation on Children at Risk, which was convened from 17–19 November 2014 in Quito, Ecuador. More than sixty church leaders, Christian practitioners, missiologists, theologians, and NGO network leaders gathered from five continents to engage in daily worship, group Bible studies, prepared theological reflections, and a variety of presentations and panel discussions.

Participants were invited to process and give feedback to these activities through a series of small-group discussions, and these inputs were documented by a team of students in order to shape the intended final outputs from the consultation: the Quito Call to Action on Children at Risk (Lausanne Consultation on Children at Risk, 2014) and this paper. As such, in a sense, all of the participants at the consultation are contributors to this paper. To read summaries from each day and the final consultation summary, as well as all of the papers presented, please go to this website: www.forchildren.com.

This paper is a compilation of sections from some of the consultation papers, summaries of some of the key ideas from the discussions, sections from some of the work done in Latin America,[1] and new writing based on the conversation during and after the consultation. The writing/editing team consisted of Dr. Desiree Segura-April, Dr. Susan Hayes Greener, Dr. Dave Scott, Dr. Nicolas Panotto, and Mrs. Menchit Wong, Lausanne Senior Associate for Children at Risk.

Introduction

Born to a teenage mother and an adopted father, Jesus started his human life in extremely uncertain circumstances. In order to fulfil the economic demands of an oppressive empire, his parents were required to leave their community and travel to Joseph’s ancestral home when his young mother was on the verge of giving birth. As a result, this descendant of kings was born in the lowly squalor of a barn. Narrowly escaping the genocidal attacks of a paranoid dictator, his young family was forced to seek asylum in a foreign country when he was still quite young.

But this was no ordinary child. This was our almighty-vulnerable, omniscient-developing, infinite-mortal God, wrapped in a blanket and crying for his mother’s milk. At the center of our faith is the mystery of how the God of the universe became a child-at-risk in order to fulfil God’s mission, which was nothing less than to change all of human history.

And now, we are at an unprecedented time in history as the Global Church rises up to seriously address the importance of children, especially children at risk. Major developments in the global church community in the past several years demonstrates a new commitment to mission to, for and with children. The 2010 Lausanne Cape Town Commitment (CTC) explicitly mentions children at risk, including children as part of the poor, enslaved, and oppressed.[2] Children have a section dedicated to them in which the people of God are asked to:

Take children seriously through fresh scholarship

Seek to train people and provide resources to meet the holistic needs of children worldwide, in the context of families and communities, as a vital component of world mission

Expose, resist, and take action against all abuse of children

The CTC embodies the priority agenda for the church in the decade leading up to 2020. In the forty-plus year history of the Lausanne Movement, it is the first Lausanne document that calls on the church to esteem the value of children and youth in the plan and mission of God.

In addition, some of the most flourishing and thriving movements and networks of the Global Church are speaking and working collaboratively on behalf of children, including the Global Children’s Forum (GCF), the Global Alliance for Advancing Holistic Child Development, the Child Theology Movement, the 4/14 Window Movement, the Micah Network Children’s Thematic Forum, and the Latin American Movimiento Juntos con la Niñez y la Juventud (Together with Children and Youth Movement).[3]

These and other movements and initiatives in diverse sectors are drawing awareness to the overwhelming issues of poverty and preventable illness afflicting children, epidemic proportions of child abuse, and widespread exploitation. The flourishing work of these key international movements, combined with the emergence of the Lausanne commitment to children in the CTC, confirms that a convergence of movements authored by the Holy Spirit is in place, and now is the time to act.

Lausanne leaders and the key players of these global movements have recognized the need to continuously engage in productive dialogue and build upon this synergistic energy to lobby for concrete and practical actions to address the issues affecting children at risk around the world. It is imperative that the church be salt and light by leading the global and biblical charge to demonstrate the love of Christ through effective, holistic, and transformational mission to, for and with children at risk.

In light of this urgency to act, the Lausanne Consultation on Children at Risk took place from 17–19 November 2014 in Quito, Ecuador. More than sixty church leaders, representatives from child-focused non-governmental organizations, missiologists, and theologians gathered from five continents. The consultation was designed to engage sustained, theologically informed, collaborative actions within the global church community to fulfil the Cape Town Commitment to all children, including those at risk. To that end, participants were invited to engage deeply and collaboratively on the task at hand. The major outputs of the consultation were the Quito Call to Action on Children at Risk (see Appendix A) and this Lausanne Occasional Paper (LOP).

The consultation had the following objectives:

- To present key theological and missiological reflections related to children at risk (CAR) and consider current and future CAR challenges.

- To describe practical ministry models that demonstrate praxis based on sound child development practice and theological reflection.

- To demonstrate collaborative models and outline broad action plans involving multi-Movement collaboration among Lausanne issue groups and global networks.

- To gather the commitments and affirmations of participating leaders to move the global church forward in seeing God’s purpose fulfilled and realized for children at risk around the world through a Call to Action and a Lausanne Occasional Paper (LOP).

In order to engage in discussion, we formulated a set of key questions to guide our ongoing conversations. The consultation was neither the beginning nor the end of this dialogue; these questions continue to shape our ongoing call to the church to reflect and act on behalf of children at risk. The guiding questions are as follows:

- What would it mean for children to be meaningfully incorporated at every level into the historical Lausanne mission statement calling the whole church to take the whole gospel to the whole world? Also, what would it mean to take the multi-directional influence of children’s presence seriously at each level?

- Children generally have relatively little power and voice in their worlds and are vulnerable to the decisions of more powerful adults in their families, churches, and communities. Considering this, how might children at risk see their place in the world, in the church, and as partners in mission? How might they wish to be ministered to, advocated for, and partnered with in the Christian community? In addition, how might the church protect them, not only from abuse in the broken and sinful systems of the world but also from potential exploitation by the church or well-meaning adults?

How might all those who work on different areas related to mission with children, such as practitioners, leaders of Christian NGOs, theologians/missiologists, seminary leaders, and denominational leaders, come together as one body focused on ministry to, for, and with children at risk? What are some examples of effective models and new ideas for collaboration and networking? How might children be included in these collaborative efforts?

- What declaration, affirmation, and intention for mission action to, for, and with children at risk can we mutually agree to as the worldwide church?

Fundamental understandings and assumptions

With these questions in mind, we call the church to explore what it means for children at risk to be viewed as strategic and indispensable to the missio Dei. We start with a set of agreed-upon understandings and assumptions as they relate to children and children at risk.

Who are children at risk?

We seek to have an understanding of children at risk as complex human beings. As part of the process of drafting the Quito Call to Action for Children at Risk, we agreed on and published a definition for the term ‘children at risk’. This was an important step because, although there is a strong intuitive meaning to the term, over the past two decades it has been used to refer to a variety of different—sometimes conflicting—ideas. Thus, the document we produced offers a brief definition of the term followed by a number of clarifying comments about different aspects of the definition.[4]

The following paragraphs present that core definition and then highlight the considerations that are most relevant to the discussions in this Occasional Paper. Children at risk are: ‘persons under 18 who experience an intense and/or chronic risk factor, or a combination of risk factors in personal, environmental and/or relational domains that prevent them from pursuing and fulfilling their God-given potential’.[5]

Notably, the document urges that while ‘virtually every child falls within this definition,[6] such thinking loses sight of the term’s purpose’. Instead, the purpose of the term is to help draw attention to the circumstances in any (but not necessarily every) child’s life that present hurdles to their development. Similarly, the definition urges a distinction between the vulnerabilities that all children face by virtue of their developmental stages, and explicitly identifies unborn children as potentially being at-risk due to maternal health difficulties, abortion, or infanticide.

Also, while many approaches to understanding children at risk have quickly moved to thinking about them in categories based on the nature of the risks they face (ie child soldiers, street children, etc.) the document recognizes that these sorts of categories seldom adequately represent the complexity of actual children’s lives. At the same time, the document also recognizes that the most consistent risk factor that is faced by children around the world is economic poverty.

One of the advantages of starting with a definition document was that it helped the group identify those issues on which we had already achieved consensus within the group. This helped us to focus the papers and discussions on the topics that were most needed to move our collective conversation ahead. This occasional paper is intended to capture some of those new topics and assertions that gained the most forward momentum at the consultation

A high view of children

With this definition of children at risk in mind, we urge the church to intentionally take a high view of all children and a high view of Scripture. Using this approach, several biblical principles should frame our conversation. These principles are based upon the biblical story of young Samuel.[7]

- All children should be holistically nurtured throughout childhood.

- The supreme story of history and life is God’s.

- God uses whom God will, including those on the margins of life, where many children find themselves.

- Children can be called by God and hear God’s voice.

- Children can be active participants in worship and service to God.

- The people of God are to respect, listen to, envision, and empower children as vulnerable agents of God’s mission.

- Each of these claims must also be true of children at risk.

While to some these claims largely speak for themselves, others may struggle in different ways with what they represent. In this document, we hope to flesh out the foundation for this perspective more concretely in biblical and theological terms. At the same time, we recognize and assert that these claims (and a number of other related observations) are the result of a set of conversations around children that have been taking place over the last few decades in different places around the world, as was mentioned in the introduction. The participants invited to the Quito Consultation were an intentional effort to draw together representation from some of those conversations, and we would be remiss if we did not observe our indebtedness to a wide variety of ideas and initiatives that those conversations have provided.

Some of those conversations include global networks and initiatives, such as the Lausanne Movement’s Issue Group on Evangelization Among Children and the resultant Global Children’s Forum; Viva’s Understanding God’s Heart for Children project; the Child Theology Movement; and the work of Christian international non-governmental organizations, such as World Vision and Compassion International. Other conversations have been more regional, including the Movimiento Juntos con la Niñez y la Juventud (MJNJ)—Together with Children and Youth Movement—and the regional versions of the global movements listed above.

Other important contributions have come from local churches and organizations that have simply caught a vision for the importance of children in church and mission and have pioneered new approaches for their engagement with children as the Holy Spirit has led them. Some denominations, such as the Nazarenes, have participated by organizing events and changing bylaws to better involve children in the fullness of churches. Universities and Seminaries have also contributed by allowing their professors to teach new classes and undertake important research and writing projects that are changing the face of scholarship on behalf of children.

These various conversations seem to have common themes. These include a desire to see children protected and respected appropriately within families, churches, and societies, but increasingly recognize some important additional themes that may seem more confrontational to some. This includes the recognition that while the nature of childhood will unavoidably change from context to context, almost all cultures are fundamentally adult-centered.

As such we tend to promote adulthood as the pinnacle of human development and society and denigrate and dismiss the contributions—both potential and actual—of children and youth. Furthermore, churches and Christian organizations in many places tend to fall into the same traps unless they are very wary. Too often the developing capacities of children are seen as a liability that justifies their exclusion rather than as an opportunity for soliciting children’s unique perspectives. This is a theme that will be discussed in greater detail in the theological foundations section below.

A second, interrelated concern is a natural result of addressing the above dilemma. That is, only once our eyes are opened to see the adult-centric nature of most societies, do we begin to understand what is possible to achieve once we consider the contributions that children can make as active participants in church and society. Furthermore, we are also seeing that making the necessary changes to encourage and empower the voices and contributions of children is not just something that helps them, it helps churches and communities as a whole. Therefore, we offer this document as an invitation to a much wider audience to join in these discussions.

Some detractors might dismiss the above concerns as being strikingly similar to the secular child rights and childhood studies initiatives that made their mark towards the end of the twentieth century. However, we see clear biblical justification for how we envision children functioning in churches and organizations everywhere, and thus believe this may be the hand of God at work in the global scene. At the same time, we recognize that cultural considerations mean that these ideas may take time to understand and apply at the local level. In any case, we remain convinced by the global participation of this conversation to date that the key concerns can spark a relevant conversation in every community that is concerned about children, which, we believe, should include all members of the Christian community.

Children as whole people

Even as we have heartily embraced children’s vulnerability, we have sometimes failed to fully comprehend their human complexity and capacities. Context and social factors are important, but concentrating solely on systemic sin and social ills is insufficient. If children at risk are to be considered full and essential members of the whole church and partners in mission, a deeper understanding of the whole child is necessary before forming a whole gospel response. The desire of those who work with children atrisk is to minister biblically, theologically, and effectively. Developing a solid theological foundation is a compelling reason for this LOP, yet it is insufficient for effective holistic engagement with children.

When working on interventions for children at risk in global settings, what might happen if we place the child in the programmatic midst and contemplate the desired impact? What does a flourishing child look like? What do children need to thrive? What does Scripture say about children? And what does human development research have to say about the well-being of children as whole people set in families and communities? By asking these questions we refuse to separate the child from the context, or the child’s human brokenness from societal brokenness and sinful systems.

How do we understand children’s development in various contexts, such as historical situations, families, communities, and cultures? How do we understand the impact of risk and resilience factors upon children’s well-being? What difference does it make if children encounter risky situations, abuse, or trauma in infancy versus toddlerhood versus childhood versus adolescence? In areas where Scripture is less overt, we may in good conscience turn to what we have learned through academic study, research, and practice that have informed our understanding of the nature and development of children. Such an integrated approach to theology and science allows for God to be acknowledged as the creator of all truth.[8]

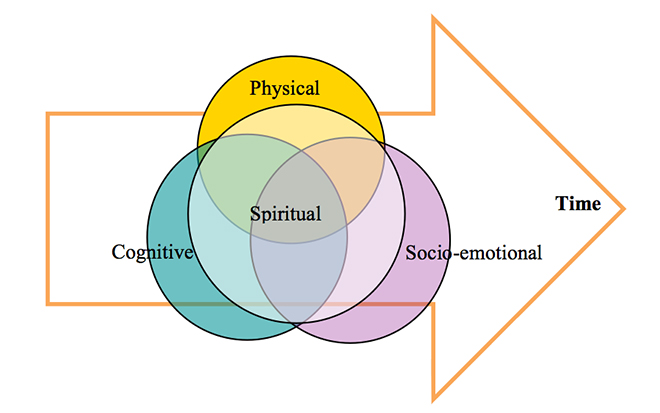

A systematic understanding of human development research deepens our understanding of the most effective ways to realize holistic transformation in children’s lives by revealing the whole child and the types of nurture, supports, environments, and opportunities that allow children to thrive. Human development research and theory suggests that four developmental categories best capture holistic child development: spiritual, socio-emotional, cognitive, and physical.[9] The items in each of these four categories seek to answer the following question: What are children’s needs for human flourishing?

These areas of human development will be explored in some detail because it may be unfamiliar to some, particularly those who are more rooted in the missions and theological worlds. We are hopeful that provision of descriptions and examples may bring to life the importance of truly integrated and whole mission to, for, and with children.

Spiritual development

Spiritual development includes changes in one’s awareness of and relationship with God.[10] Spiritual development typically is concerned with existential questions, such as: Who am I? Why am I here? What is the meaning of life? What happens after death? This definition applies to spirituality across religions and is not exclusive to Christianity. Christian spirituality asserts that the child’s relationship with God ‘is initiated by God in Jesus Christ through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in the context of a community of believers that fosters that relationship,’[11] endorsing the importance of Christ for salvation and the importance of the body of Christ (the church) in spiritual formation (see Deut 6:6–9; Eph 6:1–4; 2 Tim 3:16).

From the Christian perspective, spiritual development is unique among developmental areas because it provides the epicenter that anchors the remainder of human development. In addition, it is distinctive, in that it is not as directly tied to development over time as other areas of growth. For example, physical development follows a fairly specific trajectory and timetable, allowing for comparatively accurate prediction of timing milestones in development (eg children across the globe typically take their first steps between 9 and 12 months of age).

However, spiritual insight and sensitivity are not necessarily connected to one’s chronological age. Children may exhibit a depth of spiritual awareness that may be absent in older persons, even if that awareness remains framed in developmentally appropriate expressions. For example, research exploring spiritual understanding has been implemented for children facing their own death, indicating a quality of comprehension not fully explained by cognitive levels of development.[12]

The model below is one possible way to visually represent the centrality of spiritual development, linking the whole person and reflecting the developmental implications of a biblically and theologically grounded model of holistic development. For a list of human needs in each area of child development, co-created by a global conversation with those in children at risk ministry, please see Appendix B.

Figure 1: Interaction of Areas of Human Development with Spirituality at the Center

Physical development

Physical development includes changes in body size and proportion, brain development, perceptual and motor capacities, and physical health.[13] Health and growth are commonly included in this developmental domain, but it should also include neuro-muscular coordination, as well as large and small motor skills, which are vital for performing day-to-day tasks. (See Gen 47:12, 24; Deut 10:18; 24; 1 Tim 5:8.)

Socio-emotional development

Socio-emotional processes involve changes in an individual’s relationships with other people, changes in emotions, and changes in personality.[14] In the study of human beings, it is especially difficult to separate the emotional domain from the social one. By placing them together, we recognize that children develop in relationship with others in order to fulfil emotional needs; and that socialization is accomplished through the communication of messages, both verbal and nonverbal, that are loaded with emotion. Emotional competence is an especially important concept in socio-emotional development that has been found to be a predictor of well-being in life across the categories of relationships, school, and job performance.[15] (See Matt 19:13–14; Mark 10:13–14; Luke 18:15–16.)

Cognitive development

Cognitive development, an important piece of holistic child development, includes changes in an individual’s thinking, intelligence, and language. Intelligence is defined in a very broad sense and includes verbal ability, problem-solving skills, and the ability to learn from and adapt to daily life experiences.[16] The purpose shifts to teaching children how to learn, giving them the confidence to try new things, imparting the skills to make good choices and encouraging them to use their giftedness to meet economic needs and fulfil vocational calling. Particularly for children living in extreme poverty, opportunities to develop skills for critical thinking, effective communication, application of learning, and entrepreneurship are critical. In other words, the child needs the skills necessary to be an effective worker, businessperson or entrepreneur (See Prov 1:8; 2:1; 3:21).

Integration, synergy, and responsible caregiving

Because children do not neatly divide into categories for the convenience of intervention design, the concept of the whole child must be kept at the forefront. If viewed as biblically and theologically essential, integral mission for children will favor combining interventions to address children’s needs holistically as more effective than programs that address an isolated area of development, such as health, evangelism, or formal education.

One of the key principles of positive child development requires synergistic relationship among developmental areas. Health status, nutritional status, physical and brain growth, spiritual well-being, and psycho-social well-being of children all work together to enhance the effectiveness of each category.[17] At no time is this more critical than in the early years of childhood where neurological structures develop most rapidly and a multitude of health, emotional, and relational problems can be prevented through holistic intervention and nurture, particularly for children at risk due to poverty and deprivation.[18]

Although it is convenient to separate child development into specific areas or to engage in separate programmatic interventions by sector, this approach does not reflect the holistic nature of the person. Learning opportunities designed for children’s development touch the whole person, and engagement with children should reflect that integration. No one person, church, or program can accomplish everything that children, particularly children at risk, need holistically. Nevertheless, a mindset of holism must pervade our thinking. At a foundational level, a responsible adult must care enough to ensure that integration is taking place and that the holistic needs of a specific child are truly being met, just as each of us does with our own children. (See Gen 21:8–20; 1 Sam 1:1–2:11; 1 Kings 17:7–24; 2 Kings 4:1–36; Matt 5:21–24,35–43).[19]

A simple illustration may be helpful.[20] When a child is ill, the caregiver takes the child to the doctor. When a child is emotionally troubled, the caregiver may take the child to a counselor. For educational needs, the caregiver sends the child to school. Yet, when a child trips on an upturned stone on the path and falls down near to us, we run to that child, scoop her up, look at the wound, croon to her that all will be well, tend to the wound, dry tears, and pray for healing. . . . And we can invite her to join us in repairing the rocky path to prevent others from injury. We do this simultaneously, intuitively understanding that her whole being is in need of tender care and nurture, and the risky context must be remedied to prevent future injury.

In addition, it is important to recognize that children are active participants in their own development, and the processes of children’s interaction with environmental influences are multi-directional. To put it more succinctly, children are not simply passive recipients of others’ influence.[21] Metaphors of the child as a pilgrim, or as one dancing with God, beautifully express the proactivity of the child.[22] And human development research affirms that children are agents: active, influencing, whole, and complex persons.

In addition to holism, child flourishing requires starting as early as possible and continuing for as long as possible.[23] In other words, the responsibility of care begins before a child is born, continues until the child is able to fully embrace adult responsibilities and endures to some degree across the lifespan through interdependent, mutual support. At the very least, the greatest influencers are those who are present early in the child’s life and committed over the long-term.

What is childhood?

Another aspect of viewing children at risk as complex human beings is recognizing that there are a variety of ways of understanding the experience of ‘childhood’. Why are children often the most vulnerable group in society? The answer to this question lies in how we understand and define who children are and what place they hold in societies, neighborhoods, schools, churches, and families. How we answer the basic question of ‘what does it mean to be a child?’ will result in diverse ways of acting and viewing reality. There are different ways of understanding children and childhood and specific discourses that are derived from this. One example is the belief that children are inferior beings or people who are less developed than adults.

There are diverse conceptions of what being a child means. We do not often consider this because we take for granted that we all understand it, since all adults have lived through childhood. However, intentionally focusing on a clearer understanding of childhood is a determining factor in our work because the way we intervene in the lives of children at risk will depend on what we understand childhood to be. There are sometimes practices and circumstances of exclusion that are perpetuated in programs and structures, and this leads to the normalization of certain ways of thinking and acting. Thus, we will ask throughout this document: What place do children have in our communities and churches? Where is this defined? What types of understandings about children motivate the role they play? Do these understandings sometimes legitimize the other risk circumstances that they experience in their immediate context, such as the family, the neighborhood, or school?

The at-risk situations in which children find themselves are not tied only to their current problems, but, rather, these situations go much deeper and are, therefore, much more problematic to address. The situations children face are based also in the images and ideas that circumscribe, limit, locate, and open up their place within the community. More specifically, these images and ideas are related primarily to the adult-centric worldview that governs our societies. What do we mean by this?

Children generally have a position of inferiority in relation to adults.

There is a strongly marked distinction between the ‘things that have to do with children’ and ‘adult things’. This produces clearly marked differences in the power and value given to children versus adults (both in the family and within churches).

There are ‘normalized’ divisions between the characteristics of diverse groups that make up our societies. These are ‘normalized’ because the divisions are not discussed, but rather it is assumed that this is ‘just the way it is’. Thus, all sorts of situations are legitimized, such as mistreating senior citizens, or children, or women ‘because that’s the way it’s always been done.’

There are opposing worldviews that are described as ‘adult logic’ and ‘a child’s logic,’ and the latter is usually considered to be ‘inferior’.

In light of these concepts, in our work with children at risk we must not only take into consideration the consequences of certain practices and contexts, but we must also recognize that there are certain understandings, ideologies, and discourses that make these circumstances possible. For example, ‘if worship is viewed as an intellectual, rational activity or event, children cannot participate until they are capable of reason and conceptual thinking. If worship is primarily verbal—using volumes of words and language that are beyond a child’s grasp—then children cannot participate unless they can read well.’[24] As well, whether we realize it or not, we ourselves have often allowed these ways of thinking to be perpetuated, due to the normalization of certain understandings of the world, humanity, the church, and God.

Theological foundations for our call to action

With these fundamental understandings and assumptions as a starting point, we now turn our attention to the key theological foundations for our call to act on behalf of and with children at risk. What might need to happen for the church to conceive of children at risk as whole, complex human beings who actively participate in their own development, who grow in context, and who, although vulnerable, possess the capacity to be agents of God, regardless of age, status, or gender? We believe that this question needs addressing in conjunction with developing an understanding of the missio Dei as it pertains to children at risk.

A side-door approach turns the typical question around. Rather than beginning with the definition of a holistic gospel and attempting to insert children at risk into the missio Dei, we begin with children at risk, placing the child in the midst (Matt 18:2; Mark 9:36), just as Jesus did when teaching about Kingdom reality (Matt 18:1–4 Mark 9:33–37). In doing so, the compelling rationale for a whole person, whole gospel understanding of mission ‘to, for, and with’ children at risk emerges as a more robust and biblical representation of children as vulnerable agents of God.

We should not underestimate the importance of the progression outlined in the Lausanne declarations. Children have moved from omission, to inclusion as mission targets, to agents of mission beyond their peers. As agents of mission, children should be empowered as partners with us. As well, and no less important, the Cape Town Commitment calls upon the church[25] to respond to the pain, injustice, and oppression experienced by a billion children at risk as integral to a holistic gospel response.

In addition to the strategic nature of including children fully in the missio Dei and the missio ecclesia, children are often a rallying point not only for the church, but for the world. We grieve when children go without food, shelter, nurture, health care, education, and familial love. We become indignant when the children of Iraq are beheaded and when children are exploited for the monetary greed or sexual pleasure of adults. Like Jesus, we should be indignant when anyone, including disciples of Jesus, keeps children away from him or causes these little ones to stumble (Matt 18:6, 19:13–14; Mark 9:42, 10:13–14; Luke 18:15–16).

Those of us who have worked with children at risk over the past decades have witnessed the passion, collaborative spirit, and the willingness to cross denominational and secular lines in order to address children’s pressing needs. In this way, children at risk help us focus on what is most important, stripping away theological differences and ideological arguments to release the whole church to bring the whole gospel to the whole world. The following ideas present a snapshot of some of the most important theological concepts we have identified so far in this conversation about releasing children at risk to be vulnerable agents in God’s mission.

The whole child and the whole gospel

We can start with the concept of wholeness, reflecting upon the Cape Town Commitment and the conviction that ‘holistic ministry to and through each next generation of children and young people is a vital component of world mission.’[26] To live into the Cape Town conviction and fulfill the aforementioned commitment, we must first have a basic understanding of the child as fully human, whole, and complex, as was discussed above.

Now the boy Samuel continued to grow both in stature and in favor with the Lord and with the people (1 Sam 2:26, NRSV).

Jesus grew in wisdom and in stature and in favor with God and all the people (Luke 2:52, NLT).

These passages referring to Jesus and Samuel recognize the importance of growth in all areas of development and that nurture of the whole child is necessary for children’s well-being. The intellectual, physical, spiritual, and socio-emotional aspects of the human experience are interdependent and essential to wholeness and reflect the integrated way that children engage with life.

Extending the whole gospel to the whole child is grounded in the foundational truth of the incarnation as proclaimed in the ancient creeds of the church.[27] Most theological statements tend to concentrate on the incarnation of Jesus as an adult man, but are less likely to explore the implications of Jesus’ development through all human life stages. The relationship between the divinity and humanity of Jesus has been the focus of ongoing tension in theological circles.[28]

Contemporary Christology affirms the genuine humanity of Christ, and the Majority World theologians, who are surrounded with the evidence of oppression of the poor and marginalized, push for contextualization of Jesus’s significance for contemporary peoples and situations.[29]

Given the tangible reminders of the abhorrent situations of children at risk, these contextual questions lead us to ask: Who is Jesus Christ for children at risk today? This question may be partially answered by acknowledging the developmental phases and trajectory of the infant, child, and adolescent Jesus. Exploring this question is not meant to diminish the importance of the divinity of Christ; it is meant to push past the typical Western response to Jesus’s question of ‘Who do you say that I am?’ and the typical answers of describing ‘what’ he is and what he ‘does’.[30] Therefore, part of that push past the philosophical is to embrace the developmental nature of human beings, including the child Jesus.

Jesus not only came in human form, but in the same manner and timing of all of humanity. He, too, was conceived (albeit uniquely), born as an infant, grew throughout childhood and adolescence into adulthood. The incarnation is far reaching, even to the redemption of all of creation, including the whole of human development through the lifespan.

We do not know a great deal about Jesus’ childhood, yet we do know that he developed through the normative stages of life and that he developed holistically in all facets of humanness (Luke 2:52). Jesus lived as a body (he grew in stature), and a mind (he grew in wisdom), and a spirit (he grew in favor with God), and as an emotional and social being (he grew in favor with those around him).

The early church grasped this importance because it was instrumental in changing how the world viewed children, acknowledging them as persons, even prior to birth and speaking out against infanticide, abortion, and other social evils.[31] The early church fathers recognized the importance of Jesus’ childhood and that his developing humanity sanctified us all through developmental time. As stated by Irenaeus in the early 2nd century, ‘He was made an infant for infants, sanctifying infancy; a child among children, sanctifying childhood . . . a young man among young men, becoming an example to them, and sanctifying them to the Lord.’[32]

Yet, children, especially children at risk, remain marginalized in society. The evangelical faction of liberation theology[33] in Latin America can be helpful in recovering the humanity of children at risk and in addressing theologically-informed praxis with them. Mission with children at risk cannot be effectively engaged separate from understanding their respective contexts, developmental concerns, and human agency (eg they are actors in their own development). As Gutiérrez notes, the poor and marginalized are not preoccupied with questions about the logic and propositional truth of Christianity;[34] children at risk wonder why they are treated so poorly, exploited, abused, and demeaned. Announcing God as Father in a non-human world and elevating the child-at-risk as a child of God imparts dignity and humanity to every person, no matter what age or developmental stage.[35]

A God who cares and ultimately frees and restores the child, through individual salvation, and also from oppressive systems (eg enslavement, trafficking, endorsed abuse, inadequate educational opportunity, gender and other discrimination, etc.), invites that child into the abundant life of communion and full participation in community and in the family of God.[36] Jesus Christ, by adopting a preferential stance toward the weakest, such as children at risk, conveys that when the basic human needs of children at risk are met, these offerings are unto Christ, and if these children’s needs are ignored, eschatological judgment will come upon the negligent (Matt 25:35–46).[37]

Children and the Kingdom of God

Jesus sat down and called for the 12 disciples to come to him. Then he said, ‘Anyone who wants to be first must be the very last. They must be the servant of everyone.’ Jesus took a little child and had the child stand among them. Then he took the child in his arms. He said to them, ‘Anyone who welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me. And anyone who welcomes me also welcomes the one who sent me.’ (Mark 9:35–37, NIRV)

Jesus set a child in the midst of the disciples to teach them who is first in the Kingdom of God. What, then, is the Kingdom? The term comes from the Old Testament, when the people of Israel were faced with being oppressed by the empires in power. The ‘Kingdom of heaven’ that was coming near represented how God would intervene in response to this oppressive situation. It would be a unique kingdom, led by a Messiah, and it would achieve peace and justice. This vision is expressed in the prophetic writings and especially in Isaiah where the salvation that would come would be everlasting (Isa 51:6), a radical change would take place among the people (Isa 60), and a new Heaven and Earth would be established (Isa 60:19; 65:17; 66:22). In other words, the Kingdom of heaven would bring a holistic transformation of Israel in all areas: a fairer justice system, a more egalitarian political system, and a more community-based economy.

On the one hand, Jesus himself proclaimed and incarnated this Kingdom and, on the other hand, the Kingdom is still yet to come (Luke 17:20–24). Those who follow Jesus recognize this paradox where we see the presence of the Kingdom that transforms history today, while at the same time we have hope for its final fulfilment, which is the goal that we actively and expectantly pursue, guided by the Spirit (John 16:5–15).

The Kingdom practiced and proclaimed by Jesus was about opting for the more disadvantaged of society at that time, attending to the poor and the prisoners, and fighting against injustices in legal, political, and religious settings (Matt 5:3, Luke 4:16–20). The Kingdom, for Jesus, also meant acts of inclusion and ‘breaking’ with the customs of the time. For example, when he was in the house of Mary and Martha (Luke10:38–42), the imagery evoked is that of a master with his apprentices, a practice which would not have normally included women in the culture of that time. We also see this approach in the story of Jesus’ dealings with the Samaritan woman (John 4:1–26). The radical nature of this story not only rests in Jesus having approached a person from Samaria, whose people were disowned and discriminated against by the Jews due to their ‘ethnic impurity,’ but also in the fact that she was female. Despite this, Jesus comforted her and announced the good news.

Jesus shows that the Kingdom has come through his words and actions (Matt 12:28; Luke 11:20; 17:20). He uses the language of ‘fulfilment’ to describe his ministry and mission (Luke 4:21; 6:20; 7:22; 16:16; Matt 11:15). He presents the Kingdom as a ‘human experience’ where one is open to the grace of God (Luke 12:32). This Kingdom is not a despotic kingdom like the surrounding empires were but an inclusive and loving kingdom (Luke 6:20, 7:22; Matt 11:5).

Furthermore, this Kingdom does not belong only to an uncertain future, but, rather, Jesus Christ makes it manifest in the here and now. This is reflected by different images expressed by Jesus: pardoning sins (Mark 2:17; 22:5; Luke 7:50; 15:2; John 8:11), which was not a legal transaction or religious rite, but rather a true act of liberation from interior guilt, fear, and social exclusion, in order to reintegrate the person back into the community (Luke 19:1–10); restoring life, reflected in his ministry of both healing and the expulsion of demons, which are not mutually exclusive acts, but rather, once again, demonstrate holistic redemption; and by sharing the table with everyone without exception (Mark 2:15; Luke 7:36; 11:37; 14:1; 15:2; 19:5), a demonstration of a loving openness to all people without any social restrictions.

In summary, the concept of the Kingdom of God, which is found throughout the Bible, is characterized by the following three propositions:

God is the initiator and promoter of the Kingdom, and as such the undisputed sovereign One.

All human actions are subject to God. In praying the Lord’s Prayer, Jesus stated ‘Thy will be done’ (Matt 6:10), indicating that a person who follows the will of the Father will have access to the Kingdom of God (Matt 7:21) because everything depends on God’s will.

With the purpose of focusing clearly on the sovereignty of God over everything that was created, priority is given in the Kingdom to those who are vulnerable and weak. Jesus taught with full clarity that the Kingdom of heaven belongs to the poor and to children (Luke 6:20; Mark 10:14).

God’s reign is universal. Both the Old and New Testaments present God’s domain as king and governor as extending beyond any religious, racial, or ethnic boundaries. The mere fact of starting the Holy Scriptures with the creation of the world indicates that the action and sovereignty of God has no limit whatsoever. In addition, the Exodus, a core event in biblical faith, demonstrates the liberating action of the Lord toward those who live in oppression and slavery.

‘Little ones’ in the Kingdom

With this understanding of the Kingdom in mind, what place do children have in it? Beginning in the Old Testament we can see that those who were excluded from the people of Israel were central in the mission of God. This is demonstrated in the Bible’s emphasis on attending to and caring for orphans, widows, and foreigners (Exod 22:22; Deut 10:18; 27:17). Jesus follows this same path in his ministry, caring for the sick and widows, fulfilling through both his actions and words the preferential option of God toward those who suffer from scorn and oppression (Matt 5:1–12; Luke 4:16–19).

Children are often described as ‘God’s little ones’. God welcomes them in a special way because of their situation of exclusion and vulnerability. The biblical witness is that of a God of justice, equality, and love. When faced with injustice and those who are helpless, God acts. God is a God who is in solidarity with human pain. As such, God has a special place in God’s heart for children.

Children as theological subjects of the Kingdom

At that time Jesus said, ‘I praise you, Father. You are Lord of heaven and earth. You have hidden these things from wise and educated people. But you have shown them to little children’ (Matt 11:25, NIRV).

While Mark 9:35–37, discussed above, reflects how Jesus uses children as a metaphor of the Kingdom, Matthew 11:25 shows the active place that they have. Everything that Jesus’ followers had lived through, all of the joys and glories of their life with Jesus, had been hidden from the wise, those educated in the law, and the religious leaders of the time. Instead, it was all revealed to children. As we have seen, God’s little ones represented a central concept in the theology of Israel. For this reason, within this context, it must be understood that children were conceived as a ‘voice of divinity’, both in the Jewish tradition and in ancient Greco-Roman religiosity.

In this telling, Jesus contrasts two types of logic. The first logic is that of the wise and understanding—adults, who supposedly knew all the details and authorized interpretations of the religious documents. The second is the logic of little children. The adults represent reason, intelligence, calculation, control—all of those ideas that define the essence of ‘maturity’ and supposedly make it possible to speak with objectivity, determination, strength, and righteousness about things related to God. However, in the end, the ones who were chosen to receive the divine mysteries were children. Jesus places them as an example, as theological subjects, as fundamental to revelation.

As we know, the biblical texts are not just stories that describe a linear progression of events. On the contrary, they are occurrences that also have a very profound symbolic meaning. What does it mean, then, to view God from the perspective of children, rather than from the point of view of those who supposedly have the moral, spiritual, institutional, or academic authority for understanding God? We are able to conclude that these two types of logic present in the passage represent distinct ways of viewing God. With this we are not only referring to specific images or discourses, but, also to different ways of coming close to the divine.

Adult-centricity in our churches

Unfortunately, Jesus’ emphasis on placing a child in the midst has not often been lived out historically. The adult-centricity present in our societies often gives rise to children being victims of mistreatment, violence and exclusion, due to normalized understandings about the supposed inferiority that they have. Does this affect our churches? Sadly, the answer is yes.

We can see this adult-centric view in our ecclesiastical communities by the secondary place that children and adolescents usually have in the organizational structure of the church, and by the fact that they do not often play a leading role in activities that are usually exclusively run by adults.

From an even broader perspective, we see these dynamics in the ways that many doctrines and images of God are understood. These understandings are usually based upon an adult, masculinized vision of God that does not correspond to the biblical text and that denigrates the role of both children and mothers. As well, children and adolescents are often excluded within some practices and doctrines, such as baptism, the Lord’s Supper, liturgies, etc.

Faced with this reality, a proposal for change will necessitate challenging the social, cultural, and religious worldviews that sustain and underpin a position of vulnerability for children. In other words, children need a new place in our families, our communities, our schools, and our churches. Therefore, today much is said about children as social actors, where their capacity to choose, create, grow, participate, and have a voice is recognized. How might the church give children this new place?

Children in the center

If the church is willing to be open to this new Kingdom way of seeing life, mission, and spirituality, then we will view children as central actors in the church. We are not arguing that children should be the only ones considered from the perspective of the Kingdom. Rather, we are emphasizing that in light of the current situation of children and adolescents in our societies and churches, it is necessary to give them a more central place. Furthermore, understanding the Kingdom in this way shows us the importance of engaging with any person and any circumstance that reflects the presence of injustice and exclusion.

As we have stated, placing children in the center is about giving greater prominence to a group whose vulnerability comes from their invisibility and exclusion. Why is this important? Because this implies empowering them, recognizing their creative capacity and their right to have a voice, and committing ourselves to building a new way of viewing children. The result will be a broader vision of their situation, which will hopefully result in practical actions for fighting against the circumstances of injustice that lead to children being in a place of vulnerability and risk. This will also result in a new way of seeing the church, including examining its theologies, organizational structures, spiritualities, ministries, and how it understands living in community.

How can we build theologies that are more inclusive and sensitive to our children? The road we need to travel is to facilitate theology from the perspective of children. This means building spaces where children are listened to about matters of faith, the Bible, and the church. Of course, adults have a great deal to teach, but we can also create spaces where the understandings and images of children teach us more about God because God also speaks through them. Furthermore, the mere act of allowing them to speak and be listened to is an act of recognition and inclusion in itself, and, as such, an act of justice.

This will mean great changes in how the church recognizes itself as a community of learning. Therefore, we ask ourselves, how do we create teaching moments in our churches? Are children given opportunities to create theology—that is, to manifest their vision of who God is and how God acts—or, are they simply recipients of teachings from adults? What would it look like for children to be embraced and engaged as active agents of mission within our churches?

Children at risk: vulnerable agents of mission

One of the main propositions of this paper is that children at risk are to be embraced, engaged, and released as ‘vulnerable agents of mission’. What do we mean by this? Children are vulnerable because of their smaller physical size, dependence upon broken adults for care and nurture, and disproportionate impact of broken and sinful systems. They are also active in the development process, not passive victims in their respective journeys, and they bring that same agency to the church and mission. All too often we have relegated children to tabula rasa status—as empty cups waiting to be filled with teaching until they are intellectually able to discern doctrine, to be ‘saved’, and then to contribute as adults through financial support, use of spiritual gifts, and leadership. In a sense, they are often viewed as ‘human becomings’, rather than as fully human and fully a part of the household of Christ.

A hermeneutic of restriction

Because of children’s vulnerability and need for instruction in the ways of the Christian faith, the temptation is to be drawn to Scriptures that speak about teaching children (Deut 1:39; 6:1–3; 11:18–21; 31:12–13), or obedience (Eph 6:1–4), or disciplining children with rods (Prov 13:24). By emphasizing teaching and discipline, or even placing a child in the midst, the takeaway message can become that ministry is something adults do to children. In addition, if we focus on children at risk, we might think only of Scriptures that mention orphans and widows and Old Testament passages that demand Israel to care for them, lest they reap the dire consequences meant for those that exploit the poor (Isa 3:14–15; 10:1–2; Ezek 16:49; Amos 5:12; James 1:26–27).

At times we even overlook Scriptures where children or childhood is specifically mentioned, such as Galatians 1:15 where Paul indicates that he was set apart from birth and called by God’s grace, as was Jeremiah (Jer 1:4–10); that children are made holy by the believing spouse (1 Cor 7:14); that truth is revealed to little children (Matt 11:25–26); and that the gift of the Holy Spirit is promised to the children of those who repent and are baptized—all who are called by the Lord (Acts 2:38–39).[38]

The biblical and theological importance of children for mission provokes the church to take a high view of children with a high view of Scripture, asking what it means for Jesus to place a child in the midst of the disciples. This has been discussed fully above. However, we would like to suggest that the biblical door be opened even wider.

We propose that we truly consider children as full members of the household of Christ and His church (Rom 12:5) and open up Scripture to include children wherever we see relevance to ourselves as the body of Christ (1 Cor 12:27) and the children of God (1 John; Matt 25:40; Acts 11:29; Heb 2:11; 13:1). As may often be the case for more marginalized people, the church can be prone to a hermeneutic of restriction. By that we mean that when we consider a segment of labeled humanity, such as ‘child’ or ‘child-at-risk’, we can fail to notice children as fully a part of the household of Christ. Thus, we turn only to Scriptures where they are explicitly mentioned, which marginalizes, over-simplifies, and minimizes their full humanity.

If we remove the restriction of limiting ourselves to Scriptures where children are specifically mentioned, we move toward a posture of consulting all of Scripture and looking to those specific Scriptures for clarification within all of the biblical context.

If children are marginalized in the church until they can cognitively understand and assent to conversion in a way that adults understand and approve, then we are guilty of ignoring the parts of Scripture that affirm relationship with God and God’s presence in children’s lives. Why would the infants give praise (Matt 21:16)? Why would Jesus gather the small children and place a child in the midst as an exemplar of the Kingdom (Matt 19:14; Mark 10:14; Luke 18:16)? Why would he thank his Father for hiding eternal truths from the wise and learned and revealing them to little children (Matt 17:25; Luke 10:21)? Why would Paul say that he was called from his mother’s womb (Gal 1:5)? These Scriptures support a more nuanced and positive view of children than Augustine and others would allow.

In addition, if children are dismissed until they can cognitively comprehend salvation doctrine, we are apt to remove children from the space where ‘real’ worship and teaching takes place. This may partially explain the removal of children from the sanctuary and age segregation in the church, which would have been foreign to the early church’s concept of household[39] and community and is non-normative for much of the world. Holding to this low view of children may also contribute to harsh discipline and abuse within the household as caregivers seek to drive out the corruption they believe to be inherent in the small child. Our theologies of the child have implications and unintended consequences that may ring hollow in the context of the whole gospel message.

To understand the whole gospel as it applies to children demands that we explore all of the Scriptures specifically pertaining to children, in addition to, and in the context of, the Scriptures that apply to the entire household of Christ with the understanding that children were included in households in New Testament culture.[40] If children are fully a part of us, then we need to consider all of Scripture as applying to their lives—that they, too, have spiritual gifts and that they are called by God and hear from God.

As well, they are to be treated with the same civility demanded by the epistle of James when he admonishes disciples to follow true religion by looking after orphans and widows in their distress (James 1:27), not discriminating against or dishonoring those who are poor (2:1–6), uniting faith with deed (2:14–18), and speaking wisdom and peace (3:17). For ‘God [has] chosen those who are poor in the eyes of the world to be rich in faith and to inherit the Kingdom he promised those who love him’ (2:5). Even the poorest of children are those whom God has chosen as Kingdom representatives and are part of God’s mission as actors, not merely recipients of others’ ministry efforts. They are included in the household of Christ and were converted and baptized into it throughout the book of Acts.[41] They, too, are God’s children and participants in all that entails, not merely the biological children of men and women. With this expanded view of children and Scripture, we can also open up a wider understanding of the concept of placing a child ‘in the midst’ of our theological conversations.

An expansion of the child-in-the-midst

One day some parents brought their children to Jesus so he could touch and bless them. But the disciples scolded the parents for bothering him. When Jesus saw what was happening, he was angry with his disciples. He said to them, ‘Let the children come to me. Don’t stop them! For the Kingdom of God belongs to those who are like these children. I tell you the truth, anyone who doesn’t receive the Kingdom of God like a child will never enter it.’ Then he took the children in his arms and placed his hands on their heads and blessed them. (Mark 10:13–16, NLT)

The meaning of this passage has likely been constrained in evangelical circles by the tension between a focus on evangelization in terms of geography and quantity of souls saved versus an ecumenical focus on the mission of Christ and the Kingdom of God.[42]

Consequently, the Western mind becomes stuck on choosing between and ranking evangelism and freedom from oppression (Luke 4:18) rather than embracing a unified vision of them as inextricably intertwined. Once again, children have been the losers in adult theological wrangling. A restricted view of mission has oversimplified interpretation of this Bible passage and has fragmented evangelical thought about mission to, for, and with children, very likely leading to lowered effectiveness.

As was discussed above, the Kingdom of God has broken into history in Jesus Christ and continues to do so through the power of the Holy Spirit; and the church is the embodiment of God’s action through God’s Spirit.[43] Thus, the Kingdom is present and visible through the church and in the love and service the church does in the world,[44] bringing Kingdom reality to bear as the goal of transformation.[45] For the child-at-risk, receiving the Kingdom of God: 1) fulfills the words of the prophets who saw injustice against the poor, oppressed, fatherless, and marginalized as a violation of divine law;[46] 2) acts as invitation into the presence of Christ (Mark 10); 3) affirms that children are worthy to hear from God (Luke 10:21); and, 4) gives hope in the eschatological blessings regarding the fate of the poor (Matt 25:35–46).[47]

In Mark 10, Jesus is modeling engagement with children that is perfectly aligned with the will of the Father, as he enacts a moral image that calls forth the Kingdom of God.[48] This important passage could be interpreted to remind us of our three-fold missional task: (1) we bring children at all stages of development to be welcomed and blessed by Him; (2) we stand with Jesus in indignant resistance through advocacy and action towards anything or anyone that keeps children from Him—be they haughty or ill-informed adults, broken and sinful systems, or cultural beliefs that devalue children; and (3) we embrace children as Kingdom representatives and models, who truly have something to teach and to offer to us.

This posture requires going beyond seeing children as merely humble and lowly or as sentimental and adorable additions to our worship. We are all to understand our rightful place in the Kingdom as children of God. As adults we may celebrate our educational attainment, our relative maturity, our power and position, and our status ascribed to us through our gender, ethnicity or nation of origin, influence, social class or wealth. In this way, we differ little from the anti-Kingdom that Jesus pushed against. Yet in Kingdom reality, we are not better or higher than the child-at-risk. As human beings, we all share in carrying a God stamp upon us and in recognition of the Son-sacrifice that God bestowed upon us, and we are impelled to respond in grateful joy, offering ourselves as co-laborers in God’s Kingdom. Mere humility in responding to Christ is insufficient. Humility in allowing God to speak and act through children, even children in desperate situations is demanded.

The child in the midst as a Kingdom opportunity

The child in the midst may also represent a Kingdom opportunity for a healthier future. Because the Kingdom is both now and not yet, holistic mission with children may usher in Kingdom reality more quickly by preventing the maltreatment and exploitation that create the harmful baggage that humans carry into adulthood, causing us to continue wounding one another. The long-term effects of malnutrition, abuse, lack of education, lack of nurture and love, and seemingly infinite brokenness are piled upon children and are carried forward into ministry, the church body, and communities, compromising effectiveness and gospel witness. By investing in children wholly now, perhaps children could be shielded from at least some of the trauma and harm, preventing it from being brought forward into generational cycles of ill-treatment. By investing in holistic mission with children, we might improve the flourishing of all God’s people and the effectiveness of our transformational ministry.

To that end, it is important to cultivate and allow for the meaningful contribution of children’s Kingdom giftedness. Children are not only gifts (Gen 12:2; 28:11; 1 Sam 1:27; Prov 17:6; Isa 9:6; Luke 1:47), they are given gifts from the beginning (Jer 1:5; 1 Kings 13:2) and are to offer their gifts (1 Sam 1–3; John 6:1-14; 1 Cor 12). By recognizing, nurturing, and allowing for appropriate developmental expression that is consequential and not relegated to the sentimental, children are empowered to live in obedience to God’s call upon their lives (Judg 13:5; 1 Sam 2:11; Jer 1:5; Luke 2:43; John 6:9. Refer also to the list of children as actors in the Covenant story in Appendix C).

Offering and engaging in the whole gospel with children at risk is a means to usher forth the Kingdom. Taking us back to our discussion of holistic human development—doesn’t it just make sense that starting early and committing for the long term is a more effective way to be a part of ‘Kingdom come’? If God does indeed act in and through and with children, we are prophetic and forward thinking when we embrace the young who are with us now and who will be leading the church once we have passed on into eternity.

Embracing and engaging children at risk

We have asserted that the Kingdom of God that Jesus preached inherently affirmed the roles of children in church and mission, and we have urged all churches to reflect carefully on the ways their adult-centrism marginalizes children. In this section we take that argument further. By considering children at risk we can more clearly see how adult-centrism contributes to the risks children face, and also prevents churches from benefiting from children at risk as partners in the mission of God. Furthermore, we believe that through considering mission ‘with’ children at risk God can reveal new dimensions of mission ‘to’ and ‘for’ them.

Responding to children at risk biblically

If it is true that the gospel of the Kingdom Jesus taught prioritized care and concern for the marginalized, then children at risk deserve special concern on multiple counts. They are marginalized due to their poverty or other identity markers (gender, race, or class). They are marginalized based on their experiences (ie sleeping in public places, refugee camps, or squatter settlements; or children being treated as social outcasts due to what others have done to them, as in the case of conscripted child combatants being rejected by their former communities, or sexually exploited children being shunned). And on top of these, they are marginalized simply because they are children.

As a result, there is clear biblical justification for concern and response. We argued, consistent with the Cape Town Commitment, that this means responding to the needs of children at risk as part of our understanding of the missio Dei. The Quito Call to Action extends this commitment by conceptualizing child-focused mission in terms of mission ‘to, for, and with’ children at risk. The following section explores how these dimensions of mission are derived biblically and theologically.

Mission to children at risk

The dimension of mission ‘to’ children at risk is the most direct approach to addressing the problems of children: when adults use their power or influence to directly intervene and provide for the needs of children. Some examples include a concerned Sunday School teacher feeding children a larger snack due to fears that they are going hungry at home, a planned outreach to homeless youths in the local park, or a carefully-organized intervention to rescue children forced to beg for money on the streets.

The most commonly-cited text for mission to children at risk is found in James 1:27, where James urges churches everywhere to care for widows and orphans as a genuine expression of their faith. However, the Scriptures are laced with examples of and exhortations to care for orphans and other children on the margins. God’s concern for Ishmael after he and his mother were cast out by Abraham (Gen 21) is a clear example, as well as the strident assurance in Exodus 22:22–24 that God would personally execute anyone who exploited a widow or orphan. In fact, Psalm 68 identifies God as Father to the fatherless, and says that God puts the lonely in families. By implication, it would seem that those who follow God should do the same.

Appropriately, in the story of Mephibosheth we see King David showing mercy to a boy with a disability that might have made a competing claim to Israel’s throne. However, David’s deep bond with the boy’s father outweighed any fears of accession, and motivated the King to show extravagant generosity to the child instead (2 Sam 9). Another notable story is that of the Shunammite woman and Elisha (2 Kings 4). Here, God not only provides a son to this woman and her husband as thanks to their kindness to the prophet, but through Elisha God also brings the same boy back from the dead after an unexpected fatal illness. This last miracle is mirrored by Jesus himself in the Gospels with the daughter of Jairus (Mark 5; Luke 8).

Mission for children at risk

We engage in mission ‘for’ children at risk when we speak or act on their behalf. At the simplest level adults engage in this kind of advocacy when they intervene in family or school conflicts, lending their support to a child or group of children. However, it can also involve churches or coalitions of organizations and individuals who are determined to address problems in any society that make children’s lives harder than they should be. This kind of advocacy is sometimes overlooked by churches for fear that it is too political, and, consequently, does not belong within the domain of mission.

However, we must remember that the Bible makes frequent mention of standing up on behalf of others, including children. Psalm 82:5 uses legal language to remind us to uphold justice for orphans and those who are poor, oppressed, or needy. Children at risk often represent all four of these descriptors. Indeed, the vision of shalom presented in the Torah requires that all people are living just lives, and contrasts this with those who try to exploit others for their own gain (See Ps 7, 10, 12, 14, 15, etc.). In order for this justice to be done, all people must be willing to identify and speak out when injustice is taking place.

Jesus simplifies this interpersonal commitment, by framing it in terms of loving one another (John 13:34–35). Western evangelicals have sometimes struggled with seeing the implications of this interpersonal dimension of the gospel beyond the intimacy of individual and largely invisible emotional transactions. This is something with which evangelical strains of liberation theology in Latin America can help. Liberation theologians have always seen texts such as the words in the Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55) or Jesus’ actions with the money changers in the Temple (Matt 21, John 2) as radical statements and acts with political significance. Contemporary theologians, such as Joyce Ann Mercer, hold that the true themes of Mark’s gospel cannot be understood without appreciating the sociopolitical context of the time, and the pivotal roles that several key child figures play in his rendering of Jesus’ ministry. Therefore, a broader understanding of what loving one another means must include attending to the injustices that exists in the contexts where children are forced to live.

This means that churches should ensure that governments fulfil their legal obligations to children, and that they should see this work as an expression of God’s mission. Similarly, Christians everywhere should stand up for the rights of children who have been separated from their parents and advocate for effective laws to protect all children from obvious dangers.

Mission with children at risk

This third dimension, mission ‘with’ children at risk, is the most progressive but also the most intriguing. The biblical foundation begins with observing the various children at risk in the Bible who are obvious participants in God’s mission. The servant girl to Naaman’s wife (2 Kings 5) is a particularly good example, since she was a prisoner of war whose family was probably killed when her new master pillaged her city. Yet, despite this, when Naaman contracts leprosy she is willing to share about Elisha, which sets him on a path not just to a miraculous healing but also to spiritual transformation. As a result, Naaman abandons his Aramean gods in favor of YHWH.

The young Samuel (1 Sam 1–3), though less at-risk than Naaman’s servant-girl, is still in a difficult situation. He was dedicated to the temple once he had been weaned, leaving him outside of the protection of his family. Perhaps more importantly, this leaves him in the care of the aging priest Eli, whose parenting credentials are highly suspect. Yet, despite these conditions, God calls to Samuel while he is still a child and gives him prophetic messages that he faithfully delivers.

However, the most prominent child participant in God’s mission as revealed in the Bible is Jesus himself. As revealed in the gospels of Matthew and Luke, Jesus’ birth was surrounded with tenuous and risky circumstances. As we saw in the introduction section of this paper, Jesus himself was in many ways a ‘child-at-risk’. He was the child of a teenage mother, an adopted child (by Joseph), temporarily homeless at his birth, and later became a refugee child for a time. Once again we marvel at the fact that the God of the universe became a child-at-risk in order to fulfil the missio Dei, and this same God desires that all children participate in this mission.

Furthermore, Luke’s narrative of the boy Jesus in the temple (Luke 2:41–50) shows us that his teaching ministry did not wait to begin until he was grown. Rather, the text recounts that the adults around him were amazed by his insights and understandings even at a young age.

In each of these cases we see children who were more than machinery in the mission of God. Each of these young people were exercising their own choices in response to God’s call in their lives, even as young people, and each made a profound contribution to that mission as a result. Furthermore, each one shows that God can and does call children, even those on the margins of life, to serve God’s purposes.

Fundamental objections to mission ‘with’ children at risk

This may ultimately be a difficult lesson for some Christian adults to fully accept, even if they are open to it. This is because the prevailing mindset is that children at risk are fundamentally unsuited to the lofty task of Christian mission. There may be many reasons for this, but the primary ones are that 1) children are not yet developed, and 2) children at risk need protection.

Those who might argue that children are not yet developed might say, ‘the incomplete maturing process of a young human being means that their primary role in mission will not be discovered until they are much older. Instead, we feel we should wait until they are mature Christians to encourage their participation in mission.’

In response, we must remind ourselves that the scriptural examples of children in active mission observed above each show that God chooses to work with any person precisely at the point in their development when God wishes. No adult should second-guess God’s timing. More than this, the examples above show that there are unique roles that children can play in mission that they cannot play when they are older. Eli would perhaps not have been as open to Samuel’s innocent questions if he had been older. Jesus’ questions and the answers in the temple might have been seen as adolescent arrogance coming from an older boy, rather than the astonishing insights of a child. Therefore, we should be listening to and watching children carefully at every age and finding ways to magnify their contributions to mission.

Those who believe that children at risk need protection might assume that thrusting them into the complexity of mission seems counter-intuitive. They may have injuries—whether physical, emotional, or spiritual—that need time to heal. As a result, in some cases, mission ‘to’ and mission ‘with’ children at risk seem to be at odds. Perhaps this is a case where it will be more helpful to talk about specific kinds of risk and certain kinds of mission. Certainly, children should not be forced to confront sources of abuse, exploitation, or addiction as initial steps in their participation in mission, if ever. Nor should a child who has been rescued from an abusive caregiver, be urged to confront them.

Similarly, a teen struggling with alcohol abuse should not be encouraged to return to local bars to share their testimony with strangers. This is not surprising, since we would hardly encourage an adult to do the same without considerable accountability and support, and only if that person felt a strong call to ministry in that way. Henri Nouwen’s idea of the wounded healer can surely inform this concern. Just as adults often find that they are able to minister to those whose wounds they understand best, we can expect that children and young people might do the same, but only after appropriate healing has taken place.